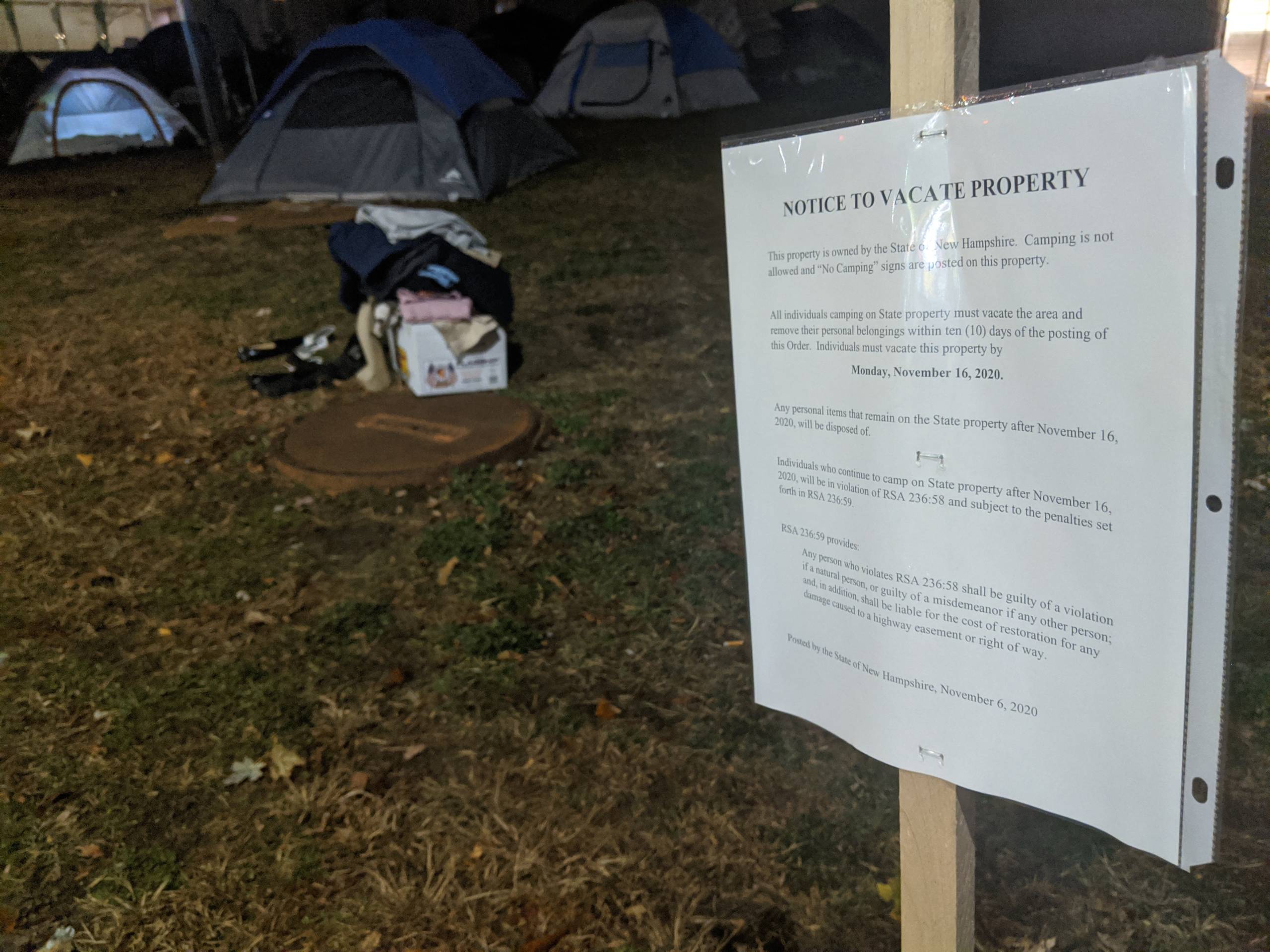

MANCHESTER, NH – The state has posted signs on the Hillsborough County Superior Court grounds advising homeless campers that they have 10 days to vacate the premises.

The signs, printed on paper covered in plastic and stapled to wooden stakes posted at intervals all around the perimeter of the property where dozens of tents have been pitched for weeks, cites NH RSA 236:58 Camping Restricted, which reads:

No person shall pitch a tent or place or erect any other camping device or sleep on the ground within the public right-of-way or on public property unless permission is received from the governing board of the governmental authority having jurisdiction over such public right-of-way or property.

The penalty, under RSA 236:59, says violators will be “guilty of a violation if a natural person, or guilty of a misdemeanor if any other person; and, in addition, shall be liable for the cost of restoration for any damage caused to a highway easement or right of way.”

Missing from the equation is where the campers should go – the state’s largest homeless shelter is in Manchester, and is operated by Families in Transition/New Horizons. It is at capacity with 107 beds between two shelter locations. There are other shelters scattered around the state, but most of them have restrictions – designated for victims of domestic violence, for family groups, mothers with children, and nearly all of them require sobriety, and nearly all of them are operating at capacity due to COVID-19 reductions in beds.

According to the city’s most recent census of the unsheltered population there were 365 people living on public property, including at the courthouse. The majority of those living rough are located on city property, a phenomenon that began in the spring after two people living at the shelter contracted COVID-19, causing an exodus from the shelter. People began pitching tents under the bridge on Canal Street and other locations around the city. Due to CDC recommendations on prevention of community spread, the state provided eight weeks of funding through the CARES Act that would allow campers to remain where they were with meal delivery, sinks and portable toilets, while the shelter made modifications and sought to expand to a second location to allow for social distancing.

At last count there were more than 30 “campsites” throughout the city, according to Manchestser Fire Chief Dan Goonan, who reported to the Board of Aldermen on Oct. 20 that a stunning majority of those living unsheltered had previous contact with mental health services, and 73 percent of those surveyed said they came to Manchester from someplace else.

The city has been at odds recently with the state over the newest encampment, which blossomed in a central part of the city behind Veterans Park on the state-owned courthouse property. The city has determined it has no jurisdiction to remove campers or take precautions for maintaining the safety or cleanliness of the property. Although Manchester Police continue to patrol the area and can enforce city laws and ordinances, the city has no jurisdiction to remove campers from state-owned property.

According to City Solicitor Emily Rice, that is one facet of New Hampshire state law that differs from many other states, as she explained during the October board meeting. Municipalities here can’t criminalize homelessness.

“If somebody wants to work on a model as exists in Las Vegas, Nevada, and other places, we’d look for a way to accomplish that legally. The law as it stands now, unless we can identify a bed for a particular individual we can’t take action against that individual, moving them or sanctioning them for not moving,” Rice said.

Aldermen Michael Porter and Pat Long have since met with the city’s legal department to that end, and are continuing to brainstorm a solution.

At the heart of homelessness in Manchester and across the state remains the lack of shelter beds, transitional housing and programs that are professionally staffed with counselors trained to assist people in rebuilding their lives and gaining the necessary life and work skills to sustain independent living.

Organizations such as the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty contend that the criminalization of the homeless is “the most expensive and least effective” resolution to the problems. In their 71-page 2019 report, “No Safe Place,’ the NLC cites a growing body of research that compares the cost of homelessness – and the burden to communities for medical, mental health, social and law enforcement services with the cost of providing housing, concluding that housing is the most affordable option.

The NLC puts the onus on the federal government to invest in affordable housing “at the scale necessary to end and prevent homelessness.” They recommend in their report funding of the National Housing Trust Fund with profits from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, money that has been given to the U.S. Treasury. They also call for housing reform legislation that would provide an annual $3.5 billion to the National Housing Trust Fund, established to build rehabilitate, preserve, and operate rental housing for extremely low-income people. It was established in 2008 and received its first allocation in 2016.

The report cites investments in solutions other cities around the country have made, like a 1 percent tax on food and beverage sales at restaurants in Miami-Dade County Florida, of which 85 percent goes to a statewide homeless trust fund, and Utah’s “housing first” program, which also includes a streamlined process for getting people the help they need.

On Nov. 5 Mayor Craig along with the state’s 12 other mayors issued a letter to the Governor calling on him to create a statewide plan for addressing homelessness, which the mayors agreed is a “top priority” all New Hampshire cities. There has not been a statewide plan for addressing homelessness since 2006, the mayors said.

In response, Gov. Sununu cited millions of dollars expended in state assistance to help people pay rent and support homeless shelter capacity.

“There’s no quick fix here but the resources and the money put toward the homelessness issue is absolutely unprecedented in the past year — not even close,” Sununu said, adding that the best approach might be for lawmakers to create and fund a permanent fixture in state government to further address homelessness.