This story is part of a series that takes a look at how school districts across the state responded to the challenges of remote learning and plans for improvements in the fall by Granite State News Collaborative.

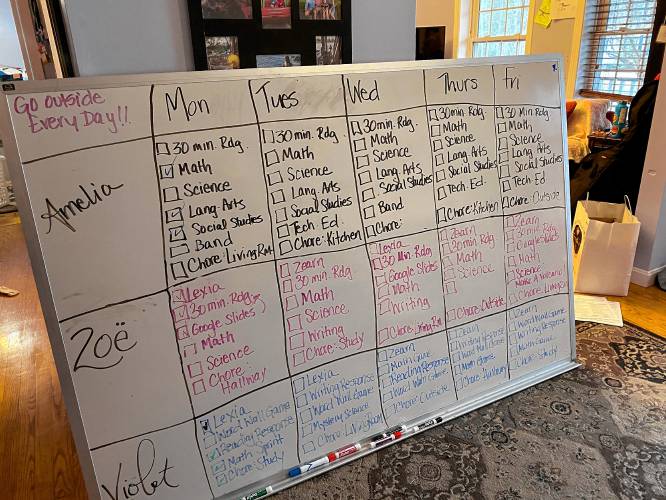

There was still snow on the ground when schools in Lincoln and Woodstock transitioned to remote learning this spring. Students, forced to learn remotely, began spending more time inside and behind a screen. But Aaron Loukes – whose job it is to make sure Lin-Wood elementary and middle school students are staying active – saw the pandemic as an opportunity for students to be more creative with their fitness.

There was still snow on the ground when schools in Lincoln and Woodstock transitioned to remote learning this spring. Students, forced to learn remotely, began spending more time inside and behind a screen. But Aaron Loukes – whose job it is to make sure Lin-Wood elementary and middle school students are staying active – saw the pandemic as an opportunity for students to be more creative with their fitness.

Some students took advantage of the snow and went skiing or snow-shoeing. Some created their own obstacle courses at home – inside or outside – and sent a photo or video to Loukes, the Lin-Wood Public Schools athletic director. He posted exercise challenges daily and encouraged students to get active and do group activities with their families.

“They loved a little bit more freedom and more of a chance to do some critical thinking and figure things out themselves,” Loukes said. “They enjoyed the family-based outdoor activities the most.”

While the coronavirus pandemic forced some teachers to learn how to teach on an entirely new technology platform it also allowed some to get creative with their lesson plans. Establishing new routines and creating new learning opportunities may have been more manageable for teachers with fewer students to attend to. That was the case in Lin-Wood.

“The size definitely [made it] more manageable. It’s allowed for even smaller group instruction,” said Judith McGann, superintendent of the Lin-Wood schools.

Administrators, teachers and parents identified clear trends in both the challenges they experienced and solutions they found, especially in the benefits of small-group instruction, advantages of technology and a new twist on the perennial quest to prevent cheating.

Lin-Wood has one of the lowest student-teacher ratios in the state, with an average of one classroom teacher or special education teacher for every seven students. This doesn’t mean that every classroom only has seven students; it does mean that there’s more teacher attention to go around. Lin-Wood educators were able track student progress and check in one-on-one with their students regularly, McGann said.

Some students at Lin-Wood had a hard time staying focused and getting work done, while others thrived in a remote environment.

“It did help the students who had social challenges. They enjoyed not having to be socially involved with a lot of people. It made them feel a little more comfortable, so they progressed in that environment,” she said.

McGann said she began to see students become more independent learners, communicate with their teachers more frequently, and take initiative on their own work. That’s a positive pattern that Bridey Bellemare, executive director of the New Hampshire Association for School Principals, noted as well.

“These are opportunities to build a little bit more of that independence and responsibility, all those soft skills that are really important to the workforce. It gets students ready for real-world learning and life,” Bellemare said. “What I have heard in the field is people are realizing we need a lot more social-emotional learning, a curriculum that’s direct instruction every single day with students of all ages, not just a guidance counselor that goes once a month into a classroom, but skills that develop us as social and emotional human beings should be taught in the classroom as well.”

Benefits of small-group instruction

Larger groups were more of a challenge for districts with a higher student-teacher ratio, said Donna Palley, assistant superintendent of Concord public schools. Concord schools have a total of 310 teachers to 4,200 students — nearly double the ratio at Lin-Wood. Some Concord teachers have classes with more than 20 students, Palley said.

While a majority of Concord school district families described their students’ remote learning experience as “mostly” or “somewhat positive,” students reported some confusion about work assigned to them. In a June survey conducted by the district, only 30 percent of students who responded said they understood all the assignments. About half (49.54 percent) understood most, and 18.73 percent understood “some.” Less than 2 percent of students responded that they understood none of the assigned work.

“I would say that teachers found that doing small group instruction using Google Meet… I think they found that bringing kids together in small groups worked really well. Meeting one on one worked really well.”

Below: Mapping NH’s Student-Teacher Ratio by District

In the spring, Concord teachers used a combination of live teaching methods with independent learning opportunities for students, but at a recent Concord school district instructional committee meeting, district officials said students and families wanted more structured face-to-face learning time to interact with their teachers and their peers.

“We need to do better with that,” Palley said.

Palley also predicted that classwork rigor fell in the spring. “We were not necessarily able to have the teaching be as robust as it was earlier. And part of it was the emergency nature of it and having to pivot to a whole new model of instruction,” she said. “Going into the next year, looking at yearlong targets are a priority.”

The Tech Connection

Of course, making the transition to remote learning in a matter of days wasn’t without challenges. Lin-Wood being a more rural district, not all students there had easy access to a reliable internet connection. And when remote learning began, students’ coursework was delivered to them so they could continue pencil-and-paper work. Not all students responded to that well, McGann said, and many preferred learning digitally, so some teachers shifted toward primarily digital schoolwork.

Although a comparatively large district in New Hampshire, Dover did not have a uniform digital learning system in place before COVID-19, unlike some other districts that were already using platforms like Google classroom. It was also not previously a 1:1 district – meaning a laptop was provided to every student – unlike Lincoln-Woodstock.

Dover school district officials have acknowledged that they are significantly behind other nearby districts when it comes to technology. Dover superintendent William Harbron said it had been a budget issue in the past but hopes that the influx of CARES funds and some savings that came with remote learning in the spring should get the district up to speed by the fall.

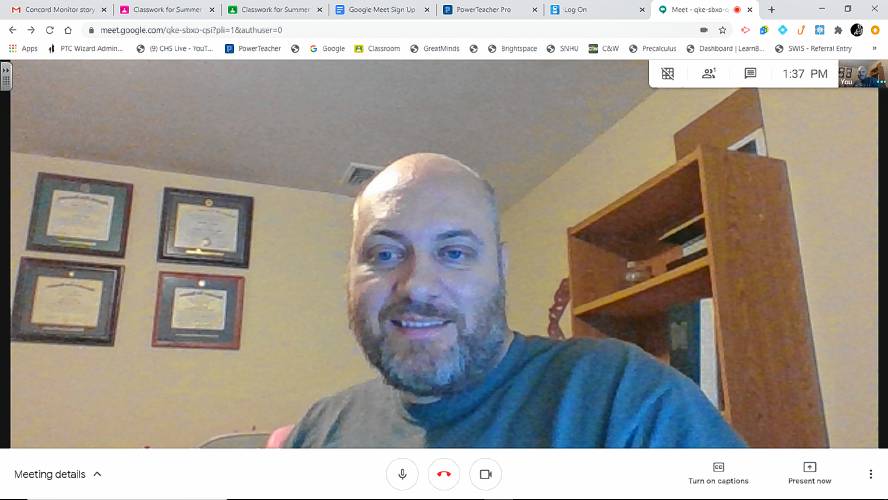

John Argiropolis, a Dover High School math teacher, said finding what worked in a remote classroom took time. He started with daily live meetings, but soon found that narrated screen recordings that showed how math problems were done were a better option because he could simulate what a class would typically look like. It also took time to understand how to set up one-on-one Google Hangouts with students, which he found were beneficial to those who took advantage of them.

“What was cool about that was I could finally have interaction with students. It was finally like a real classroom, I could have cues from students,” Argiropolis said. “Definitely, any situation where the student could interact with the teacher was better.”

Parents over-helping, students cheating

Several educators, including Katrina Esparza, principal of Beech Street School in Manchester, have also acknowledged that some kids have been getting a lot of help from parents on school assignments.

“It’s easy to tell because I could watch all the files [in the online learning platform] as they’re moving – which is really creepy,” Esparza said. “But if [a student’s] files are being completed in record time, it’s clearly not the first-grader doing the work.”

One solution to that phenomenon could be borrowed from universities that have turned to digital proctoring services – which can range from humans monitoring students via webcams, to software that allows the takeover of a student’s browser, to facial recognition. But this can come with its own set of problems, as some worry that these options violate student privacy. Others have requested that students submit videos of themselves taking exams, or for more quantitative subjects, have required that students show and submit their work.

Julie King, superintendent of schools in Berlin, says figuring out how to give reliable tests that will gauge students’ abilities will be a major priority next year.

“Some of the teachers quickly learned that the students were receiving a lot of assistance from parents, especially the younger ones,” King said. “We talked about starting fresh this year, how we would handle that differently. Grade 1 teachers know when they’re talking about remote instruction, there will be some expectations from parents: We want to see what the child’s ability is, not the parent’s ability.”

Well-intentioned parents over-helping may be a problem in younger grades. For older students with more tech-savvy, it may be tempting to use the Internet, instead of their own learning, to find the answers on certain tests and assignments. One teacher interviewed for this story said he and his colleagues suspected some students were using computer software to generate answers and cheat on tests or having other people take tests for them.

Harbron, the superintendent in Dover, acknowledged that cheating is an issue the district is aware of, both in virtual and face-to-face settings. He says teachers will be reading Generation Z Unfiltered, a book by Tim Elmore, to help them better identify signs of cheating. “This will be part of the training that the secondary schools will include in their professional development at the return of school,” Harbron said.

Looking ahead

As districts across the state ready themselves for the coming school year, most are preparing, if not outright planning, for three scenarios: In-person, fully remote, or a hybrid of the two. To that end, officials are looking to lessons learned to improve components of the remote learning experience.

In Dover, for example, one teaching method that was found to be successful with students and families was a “menu” of subjects from which students could choose to work independently. Should Dover be fully or partially remote this fall, Superintendent Harbron thinks that option will remain.

Palley, from Concord, said students can expect a mix of synchronous (real-time) and asynchronous learning with a bit more structure, should Concord schools be partially or fully remote again in the future. “I could imagine having a particular kind of writing lesson on Monday, and then on Tuesday, I’d be at home writing,” she suggested.

Even looking years ahead, after the pandemic finally comes to an end, superintendents see the use of technology and remote learning as a method that’s here to stay. If a child needs to stay home from school for health or other reasons, they could do their schoolwork online. Teachers could work with students from their homes on snow days. Bringing laptops home every day could help encourage communication between students and teachers.

“I think it’s going to be much more prevalent,” McGann said. “And now, she noted, all the state’s teachers and students have had experience with it, so it won’t be brand new in the future.

Hilary Niles contributed to this report.

Coming tomorrow: Story 5: Districts Had Trouble Tracking Student Progress Remotely

Coming tomorrow: Story 5: Districts Had Trouble Tracking Student Progress Remotely

⇒ Click here for an overview of the series.

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.