Did you ever wonder why we’re here?

Not here on Earth. I’ll leave that question to deep thinkers, the major Greek philosophers like Aristotle. And Sophocles. And George Copadis.

I mean did you ever wonder why we’re here in Manchester?

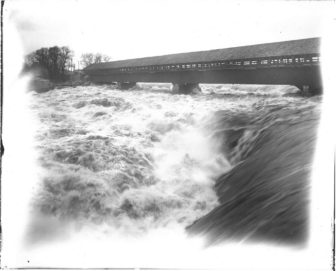

The answer’s pretty simple. Just follow the mist that’s hovering over the city until you get to the place that the Rev. Cotton Mather once referred to as ”the hideous falls of Merrimack River.”

Now Cotton Mather wasn’t exactly a million laughs – I think he invented the hair shirt – so it’s not surprising that this weenie from Massachusetts would look upon this thundering example of nature’s splendor – the single most important factor in Manchester’s eventual existence – and proclaim Amoskeag Falls to be ”hideous.”

Fortunately, more important people have weighed in with more positive reviews about the site once known as ”Namaoskeag.” Like me, for instance. Given the difficulty I have encountered with stairs in years past, I consider myself to be something of an expert on spectacular falls, and Amoskeag certainly qualifies.

Our good friends at the Public Service Company of – oops, I mean Eversource – say that on a busy day, 25,000 cubic feet of water goes roaring over the dam. It’s difficult to comprehend that staggering volume unless you have a teenager who takes several showers a day.

Unfortunately, the water passing over the dam can’t be used to generate a single watt of electricity – troubling, given my last bill – but the earliest inhabitants of the Merrimack Valley didn’t need to harness the power of the falls. They were content to harvest its bounty. And what a bounty it was.

”The rivers, rivulets and brooks were literally full of salmon, shad, alewives and eels,” C.E. Potter in his “History of Manchester,” “and at Amoskeag, they had every facility for taking fish.”

“The salmon and shad were taken by nets at the falls. In the basins below the falls, where the fish would rest after futile attempts to scale the falling water, they were scooped out with nets and weirs.” Other Indians, ”glided upon the surface of the pool and took the entrapped fish with spear or net as suited their convenience or fancy,” Potter noted.

It was the same with the alewives, a type of herring which – when pickled – tickled the taste buds of Indians and settlers alike, but – you’ll have to forgive me here – I just can’t quite get past this whole eel thing.

I love salmon. You could probably coax a plate of shad in front of me. You might, at gunpoint, even get me to sample some poached alewives. But eel? Just reading about the eel bounty around Amoskeag Falls gives me the willies. They were so plentiful they became known as ”Derryfield beef.”

”And it is no wonder,” wrote historian Fred Lamb, ”for enough eels were salted down in a single year to be equal to not less than three hundred head of cattle.

”There was one great advantage to the lamprey eel,” he added. ”It had no bones except in the head and as that portion was never eaten, it made safe food for children.”

How much of a treat were eels? A fellow named William Stark wrote a poem about Manchester for the city’s centennial celebration and his eel fixation was so great – I’m thinking something Freudian here – he devoted eight entire stanzas to the slimy critters. Here’s a sample:

”From the eels they formed their food in chief,

And eels were called the Derryfield beef!

And the marks of eels were so plain to trace,

That the children looked like eels in the face;

And before they walked – it is well confirmed,

That the children never crept but squirmed.”

A steady diet of eels would be hard for us to swallow today, but it does go a long way toward explaining the rampant rum consumption amongst the earliest settlers of Manchester.

As was the case with the Indians, Amoskeag Falls was the magnet that brought those white settlers to this area for good around 1719. Naturally, Massachusetts made a feeble attempt to claim the falls, but when boundaries were assigned and townships divided, the falls were deemed neutral territory – like Switzerland – because their finny bounty was critical to all.

The ingenuity that our ancestors demonstrated in fishing the falls eventually gave way to another sort of industry entirely, proving even further that, if the most important natural feature of Manchester is the Merrimack River, the most important natural feature of the Merrimack River is the Amoskeag Falls.

It was there that the great Pennacook Chief Passaconaway presided over tribal ceremonies. It was there that the Rev. John Eliot preached to the Indian tribes. It was there that Archibald Stark raised the boy who would become a hero of the American Revolution and it was there that Samuel Blodgett stood and gave voice to his vision.

”I see a city,” he said, ”on the banks of the Merrimack by these Falls.”

We are the embodiment of that vision, those of us who call this hamlet home, and in the rush of everyday living, it wouldn’t hurt to take a minute to visit the falls, just to pause and ponder the rush of water instead.

John Clayton is Executive Director of the Manchester Historic Association. You can reach him with your historical (or existential) questions at jclayton@manchesterhistoric.org.

You’re one click away! Sign up for our free eNewsletter and never miss another thing

You’re one click away! Sign up for our free eNewsletter and never miss another thing