Advice for navigating transitions in work, life, and relationships from Dr. Loretta L.C. Brady and her team members at BDS Insight.

I know it’s been some time since this column ran but as I reflect on the most recent presidential and vice presidential debates, I feel I have some actual clarity to offer in times of chaos. Full disclosure: I am partisan, and while I didn’t support the Democratic nominee during the primary, I am certainly “with her” now. That said, what I offer below represents the synthesis of several lines of research that address issues of bias, cognitive science, social dynamics, organizational effectiveness, and developmental research. It also reflects debates and best practices currently identified in criminal justice reform and mental health literature.

When Mike Pence, Republican Vice Presidential nominee, said during the Vice Presidential debate, “Enough of this seeking every opportunity to demean law enforcement probably by making accusation of implicit bias every time tragedy occurs,” I found myself yelling at my TV and typing furiously on my own Facebook page.

In making a statement that was intended to show support for law enforcement, he also suggested that acknowledging implicit bias is a negative, one that would “demean” police and weaken community trust. It suggests that those with bias are “weak” and that there is something one can do or be that can immunize them to the bias readily available all around them.

Bias in this case refers to the concept that each person has beliefs and expectations they use in making social judgements and that these show unintended preferences for people or situations that conform to our preferences. Mr. Pence suggests that ignoring unconscious preferences and their impacts in a variety of social interactions – including interactions by and with police – somehow improves officer safety and order. He sees this as the best path to justice system reforms. And Mr. Pence makes it clear that there aren’t many reforms needed right now – except better enforcement or targeted (i.e. “stop and frisk” profiling) patrolling.

Why does it infuriate me that Mr. Pence isn’t willing to acknowledge the role implicit bias plays in our current national conversation around race and policing?

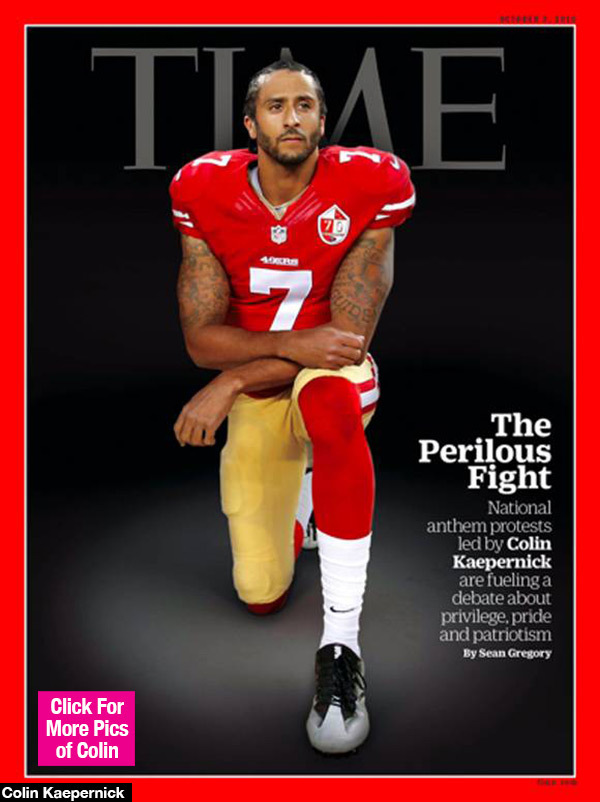

What the protests over the national anthem that are occurring within many sports teams highlight is the tension people are experiencing between rights and responsibilities of citizenship. On one hand, those who practice their right to dissent during a patriotic display are challenged, while on the other hand responsibility to respect and honor the sacrifice of our nation’s veteran’s is seen as an important responsibility for engaged citizens. The focus that should be aimed at implicit bias is costing all of us solutions and resolution: Implicit bias would open up conversations and solutions that would improve access and enjoyment of our rights while improving our ability to fulfill our responsibilities.

What the protests over the national anthem that are occurring within many sports teams highlight is the tension people are experiencing between rights and responsibilities of citizenship. On one hand, those who practice their right to dissent during a patriotic display are challenged, while on the other hand responsibility to respect and honor the sacrifice of our nation’s veteran’s is seen as an important responsibility for engaged citizens. The focus that should be aimed at implicit bias is costing all of us solutions and resolution: Implicit bias would open up conversations and solutions that would improve access and enjoyment of our rights while improving our ability to fulfill our responsibilities.

Failing to consider the role implicit bias plays in our culture means several useful solutions can’t be considered in addressing these challenges.

Addressing these challenges would allow communities to address both aspects of our national heritage and legacy. Increasing awareness and offering interventions to address bias results in attention being paid to individual professional and community responsibilities.

Attention to bias – and reducing it – would also improve everyone’s rights to expression, dissent, and pursuit of happiness. If changes in bias are sought, and policies put in place to address the impact such bias has created, then we improve the rights of all of us in a society where law enforcement has specific responsibilities, specific competencies, and specific development plans to reduce the fall out from implicit bias.

What Mr. Pence does not understand is that acknowledging the reality and the role of implicit biases in guiding behaviors and beliefs actually results in more actionable and effective solutions than would ignoring these things.

Acknowledging and assessing bias shifts the conversation about law enforcement as individual actors, from “This is a result of rampant individual racism” (i.e. there are just a few bad apples) to “This is a result of insidious and pervasive cultural programming” (our apple harvest process is creating problems); and it shifts community solutions from “Let’s fire them all,” to “Let’s train for skill and tag for accountability.”

If other professions took the approach to reducing accidents, bad actors, and unexpected outcomes that law enforcement has recently taken, we would see full analysis of black box recordings; we’d see independent and objective reviews of actions with coachable moments provided to professionals with recent incidents; we’d see national panels convened to tackle issues of standardization and innovations that could reduce the amount of lethal contact experienced in patrols, crisis or wellness checks, domestic violence or mass casualty events, even scripts distinguished for child or multilingual populations.

But at present these types of comprehensive efforts are absent. And part of this is due to our failure to attend to some of the core mechanisms of action taking place in these interactions.

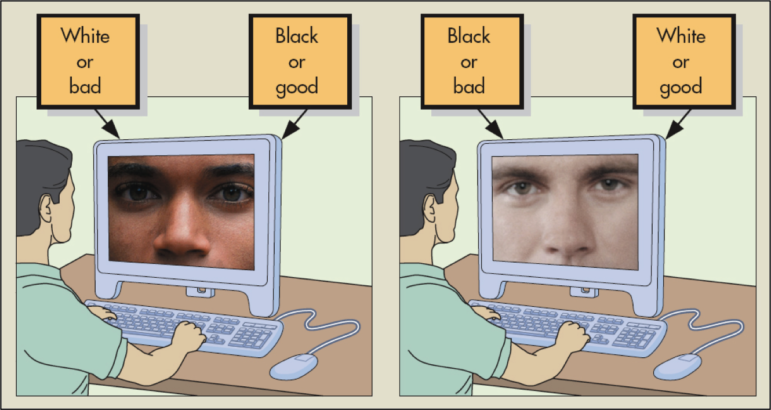

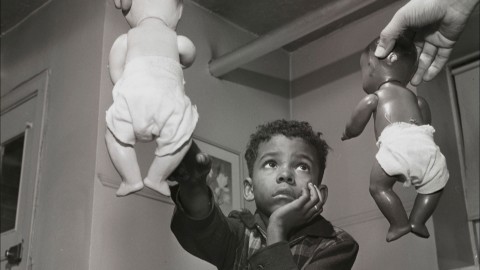

We must look first to the extensive data that has been collected over the past 17 years. In 1998 studies looking to measure differences in reaction time to a task called “Implicit Association Test” revealed consistent and profound differences in how quickly and reliably people assigned categories to faces that reflected that of a white man and that of a black man. When differences were captured showing people sort positive words more quickly when presented with a white man’s face and they sorted them more slowly and less accurately when presented with the face of a black man, researchers were able to confirm subtle differences in automatic processing. Later studies revealed bias for race, gender, size, attractiveness, immigrant status, sexuality, gender identity, and ages. Today, the original data is available to researchers and the IAT tests are available to the general public if they also agree to have their data used by the researchers at Project Implicit.

What would attention to implicit bias’ role look like in creating a program to address bias? At both an individual and group level, addressing implicit bias requires self awareness, usually through assessment. It further requires intentional seeking of counter-programming messages, efforts to educate oneself on justice movements, historical laws and policies, as well as examples of counter-biased images, stories, and communities.

What would attention to implicit bias’ role look like in creating a program to address bias? At both an individual and group level, addressing implicit bias requires self awareness, usually through assessment. It further requires intentional seeking of counter-programming messages, efforts to educate oneself on justice movements, historical laws and policies, as well as examples of counter-biased images, stories, and communities.

It would also require us to carefully consider where implicit bias has potential to influence outcomes that advantage or disadvantage others and to seek changes in workflow or work design that limit the potential impact.

One example comes from technology firms seeking to counter the effects of stereotypes of women technologists: resumes were stripped of gender identification cues so that initial candidate selection was less likely to be influenced by bias. Other strategies include presenting positive images and messages to counter a bias; researchers have found some benefit from intentionally programming media to present counter bias messages. Understanding when people are most vulnerable to acting in accordance with their biases would help us reconsider work design for police officers. Shift structures, partner rotations, and refined response protocols might all be in need of revision to accommodate what we know about the effects of fatigue, emotional dysregulation, and the amount of cognitive complexity involved in responding to crisis incidents.

One example comes from technology firms seeking to counter the effects of stereotypes of women technologists: resumes were stripped of gender identification cues so that initial candidate selection was less likely to be influenced by bias. Other strategies include presenting positive images and messages to counter a bias; researchers have found some benefit from intentionally programming media to present counter bias messages. Understanding when people are most vulnerable to acting in accordance with their biases would help us reconsider work design for police officers. Shift structures, partner rotations, and refined response protocols might all be in need of revision to accommodate what we know about the effects of fatigue, emotional dysregulation, and the amount of cognitive complexity involved in responding to crisis incidents.

Acknowledging implicit bias means that we also acknowledge the contextual factors that increase or decrease the likelihood that it presents itself. We understand bias is more likely during times of fatigue, hunger, or irritation (let’s take a look at health status and wellness efforts for law enforcement officials); we know it is more likely when primed for stereotypes (why we take language at work and images on target photos so seriously); and we know it is more likely when repeated stress exposure, or repeated exposure to negative experiences happen (so we pay attention to work design, schedules, rotation of duties, and community resident requirements and community engagement requirements).

Finally we know implicit bias is more likely to go unnoticed and unchallenged when our workgroups are comprised of people with great similarities; diversifying teams or units really can reduce impact of implicit bias. There are so many benefits we already know would come from improving individual attention and awareness of the impact of implicit bias.

So, yes Mr. Pence, there really is implicit bias and the greatest gift it gives us is a road map for constructive and meaningful police reform; reform that improves quality of professional life for law enforcement officers, and improves effectiveness and accountability within communities. It provides actionable and measurable targets for reform that are likely to satisfy those seeking justice and transparency, while bolstering the effectiveness and attractiveness of law enforcement careers.

Racism is a ghoul that continues to rob us of our potential. Understanding the impacts continued and unacknowledged racism has had on all individuals is nothing to fear; facing and addressing what haunts our collective community is the only way forward toward common solution. In the words of the summer blockbuster, “We ain’t afraid of no ghosts,” and we shouldn’t shy away from naming what needs to be named.