LONDONDERRY, NH – Heroin has been virtually supplanted by fentanyl in the New England black market for narcotics. So why do buyers and sellers of the drug still call it heroin?

When Londonderry police officers interviewed Dana Dolan last November at the RMZ Truck Stop, they already had a pretty good idea of what happened to the 21-month girl who was found dead in her parents’ pick-up truck.

Dolan, 25, was a friend of the parents Mark Geremia and Shawna Cote. All three shared something in common: they were addicted to opioids. Over the course of the interviews, the subjects referred to fentanyl, heroin and Percocet. But heroin was quoted far more commonly.

While Geremia and Cote were less than honest with police during the initial interviews, according to police reports, Dolan told police what they believed to be the true story.

Dolan described a trip down to Lawrence, Massachusetts, with the three adults, two young girls, and an ATV to trade for 10 grams of “heroin.”

At multiple times during the interview, Dolan referred to the drugs as heroin. However, the lab tests on powdered residue found in the car, the child’s clothing and a book they snorted the drugs off of came back positive for fentanyl. The state Medical Examiner’s office ruled the girl’s cause of death to be acute fentanyl intoxication.

There was not a trace of heroin found by investigators.

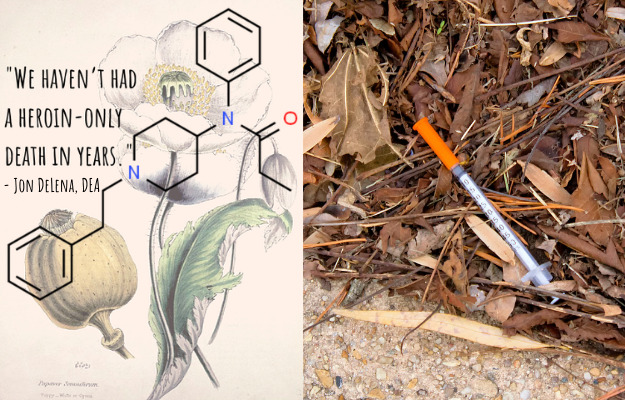

Heroin and fentanyl are two chemically distinct formulas of opioids. But buyers and sellers often use the terms interchangeably.

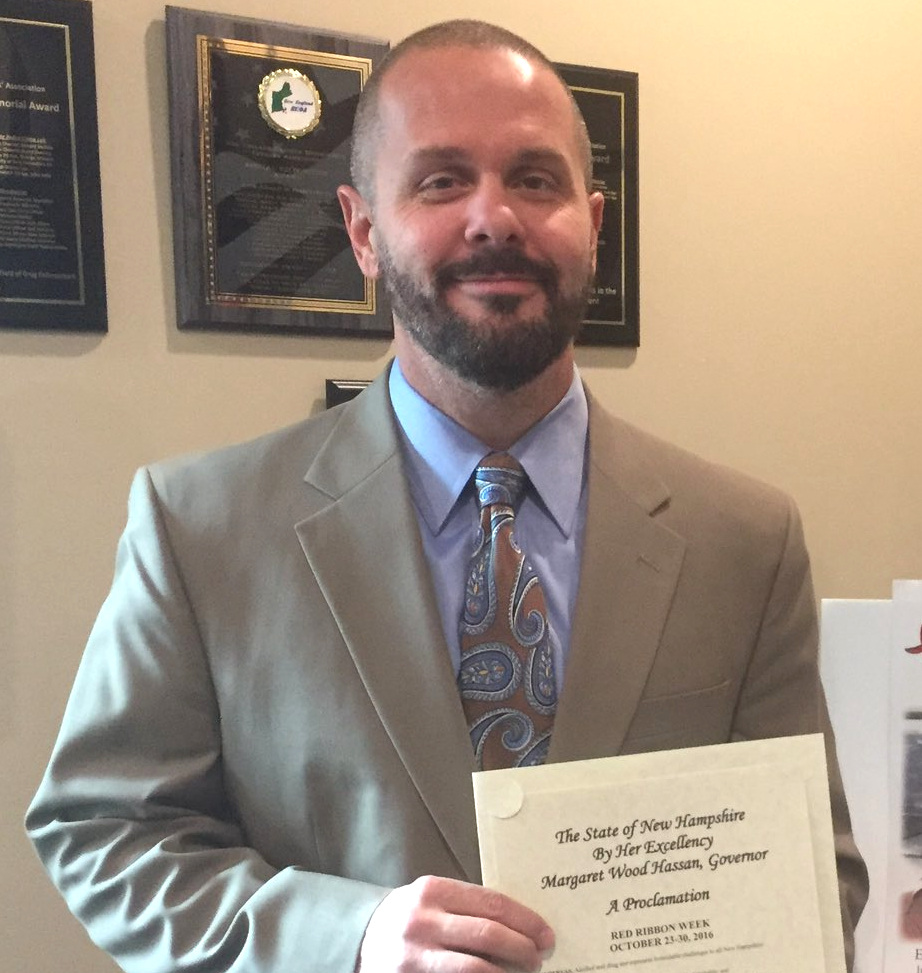

“It’s like when people call certain soft drinks Coca-Cola, and it’s not Coca-Cola,” said Jon DeLena, Associate Special Agent in Charge (SAC) for the Drug Enforcement Administration New England field division.

There are similarities, to be sure. Both are used as painkillers and sedatives, both highly addictive and both are ingested in powder form or injected via syringe. But fentanyl is completely artificial, several times more potent and therefore more deadly.

But the persistent use of the name “heroin” is even more noteworthy when you take this one simple fact into account: almost none of it is heroin, at least here in New England. Other parts of the country are still in the early stages of that transition.

“We haven’t had a heroin-only death in years,” DeLena said, referring to the toxicology results in overdose fatalities.

Heroin may sometimes be mixed in with fentanyl, but nowadays it’s rarely alone.

The New Hampshire Medical Examiner’s office has counted zero overdose deaths caused by heroin alone so far this year, in 2020 and 2019. In 2018, there were two heroin-only deaths out of 471 overdose deaths.

According to the New Hampshire State Police Drug Lab, heroin was the second most prevalent drug tested by the lab, after cannabis, in 2014 with 1,197 samples tested. That’s about 22 percent of all drug samples tested that year.

By 2020, only 199 (about 4 percent) of the samples tested included heroin. Of those 199 samples, only 18 (0.35 percent) were pure heroin.

Over that period, cannabis became a less tested drug because possession was decriminalized under a certain quantity in New Hampshire in 2017, and fentanyl rose to become the most prevalent drug tested, with 1,593 samples tested in 2020.

DeLena said for at least the past couple of years, every New England state has seen illicit fentanyl almost completely supplant heroin in the illegal opioid market, and New Hampshire was one of the first places to see this shift.

While fentanyl was still new, its dangers were not as well known.

“When fentanyl first entered the market, the retail distributors really didn’t realize how potent it was. They were overdosing everyone,” DeLena said.

DeLena thinks addicts and traffickers know the difference between heroin and fentanyl, and that most recognize it’s all fentanyl now. But the heroin moniker dies hard for a number of reasons.

For one, it creates an association in the mind of drug users as something relatively safer, compared to fentanyl. DeLena remembers one dealer who tried to capitalize on a perceived demand for heroin about two years ago when they colored fentanyl to give it a heroin-brown tinge and marketed it as heroin.

“That was just a one-off,” DeLena said.

The nomenclature is also easily transferable since DeLena says the distribution lines for intravenous opioids remain largely the same. So whether you call it heroin or fentanyl, you’re going to the same source.

And while heroin may roll off the tongue more easily than fentanyl, most consumers are either using coded language or not even mentioning it by name when arranging to buy some.

“In those lanes of distribution, you’re not going to accidentally get methamphetamine or cocaine,” DeLena said.

He said fentanyl is likely going to remain heroin’s replacement, since it can be made using chemicals provided to them by Chinese criminal organizations. Heroin, conversely, requires a whole agricultural element — to grow poppies — which is time-consuming and labor-intensive.

The only reason heroin would ever make a comeback, DeLena said, was if the primary distribution of precursor chemicals required in manufacturing fentanyl were severely disrupted.

While the black market has grown more accustomed to fentanyl, it’s still no less deadly.

Overdose deaths haven’t decreased much in New Hampshire. The last few years have seen overdose deaths drop slightly from a height of 490 in 2017 to 415 in 2019. Preliminary numbers for 2020 show death counts remained virtually the same at 413.

Meanwhile, the Centers for Disease Control say the nation reached a record 81,000 overdose deaths in the 12 months leading up to May 2020.

DeLena says its inherent dangers lie in the fact that only a miniscule amount can kill, and there’s no reliable way to ensure it’s evenly diluted in whatever cutting agents the dealers mix it with.

That hasn’t stopped Mexican cartels from continuing to manufacture the stuff, and even more troubling for DeLena, using sophisticated marketing strategies to create new customers, even among the country’s youth.

The latest development in that arena has been the creation of a pill form of fentanyl that cartels are distributing now. They’re designed to look almost exactly like pharmaceutical products like Oxycodone, Percocet or Xanax. Even veterans in law enforcement can’t tell the difference by looking at them.

The idea is to hook people on the drugs through a delivery method that people believe is safer. And what’s safer than medicine? After they’re hooked, the addicts will upgrade to buying the powder form for snorting or injecting.

“We have an entire population of people who aren’t ready to put a syringe in their arm,” DeLena said.

In a way, this is mimicking the way the opioid epidemic spread like wildfire in America in the first place, with the widespread overprescription and diversion of opioids like OxyContin. But since governments have tamped down on those industry abuses, cartels have had to create their own version of “prescription” opioids as the new gateway drug.

Crystal methamphetamine has also been marketed by cartels in recent years as a sort of counter-balance for opioid users who use the stimulant to get them up and be productive during the day. DeLena said the new batches of meth being manufactured by the cartels are coming with sales pitch instructions.

“I believe that at the cartel level they were sending samples of methamphetamine to their distribution networks … and saying this is how you’re going to do it,” DeLena said.

He said they’re even making a pill form of crystal meth that is made to resemble Adderall. DeLena believes this is a direct effort to target young people, who often use Adderall as a study drug.

Illicit drugs have many names, but it seems the medical brand names have real staying power.

Fentanyl was first developed by Paul Janssen and approved for medical use in the 1960s, sold through his newly formed company Janssen Pharmaceuticals, mostly using other brand names.

And in 1895, Bayer led the commercialization of diacetylmorphine as an over-the-counter drug using its own popular trade name: Heroin.