MANCHESTER, NH – About once a month, Manchester resident Jackie Spenard gathers up several bags and boxes of recyclables, takes the elevator down to her apartment parking garage, and makes the six-minute drive to the Drop-Off Facility on Dunbarton Road.

“I can’t go to Hannaford to buy groceries without coming home with so much plastic,” she said.

A passionate environmentalist, Spenard is cautious about what she buys at the store. She keeps two metal straws in her pocketbook. She even brings her own containers to restaurants to avoid using styrofoam for leftovers.

However, curbside recycling pickup is not provided at the River Road apartment building Spenard moved into a few years ago—so she’s taken matters into her own hands by personally delivering her recycling to the Drop-Off Facility.

“One day I was going down into the garage to put my recycling in my car. This lady walked by and asked what I was doing. When I told her, she said, ‘It doesn’t get recycled. It’s a waste of time.’ Two people at my church have said the same thing.”

So where do curbside recyclables go?

According to a 2022 report from Beyond Plastics, an environmental justice group in Bennington, VT, “less than 6% of plastic waste is recycled and the other 94% is disposed of in landfills, burned in incinerators, or ends up polluting our ocean, waterways, and landscapes.”

In 2018, China enacted regulations that severely limited further importation of recyclable materials. At the time, the U.S. was heavily dependent on China for waste management. In 2017, 31% of all U.S. scrap commodities were exported to China.

“China was receiving a ridiculous amount of recyclable materials that couldn’t even be recovered. They were overwhelmed over there with the amount of plastic,” explained Chaz Newton, Manchester’s Solid Waste and Environmental Programs Manager. “It was often going into a landfill anyway.”

Ward 2 Alderman Will Stewart served as chair of the city’s Special Committee on Solid Waste Activities during this period.

“At the time, communities across the country were grappling with a very big increased cost to recycle, based mainly on China,” explained Stewart. “They were getting a lot more stringent on what they would and would not accept.”

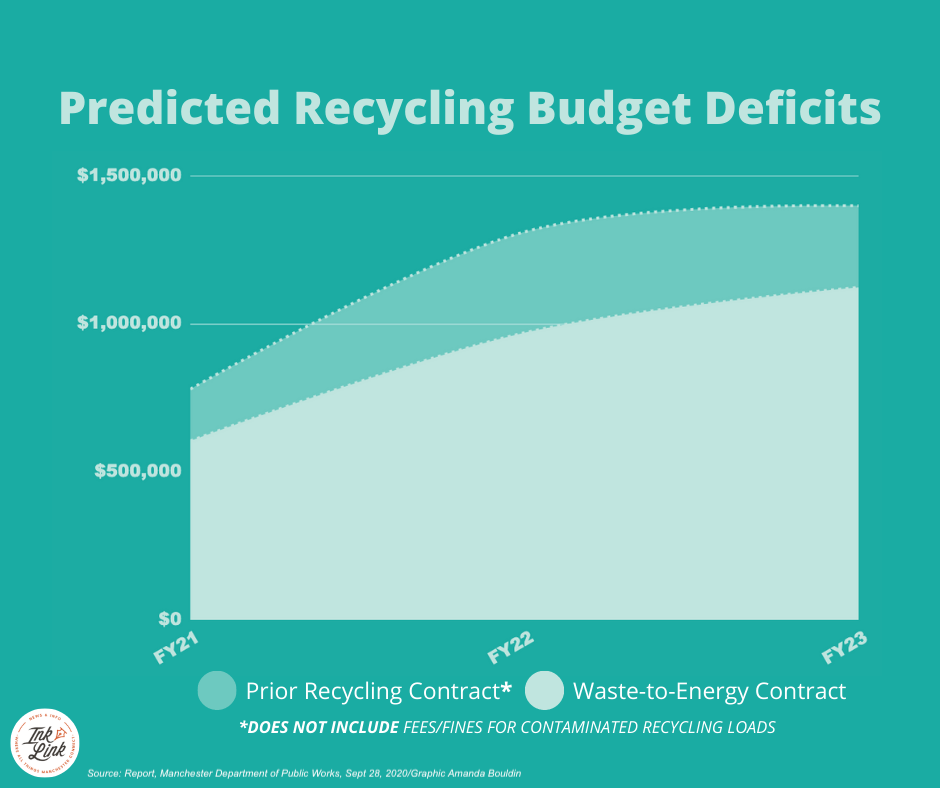

As the world grappled with the financial impacts of China’s Operation National Sword, Manchester was insulated by a recycling contract with a fixed rate for recycling regardless of issues such as contamination. With this contract expiring in 2020, Manchester stared down a nearly million-dollar increase to annual recycling costs.

“In that first year, we’re talking an extra $800,000,” said Stewart. “We always have to be balancing all of the interests across the city—teachers we could hire in city schools, more road miles that we could pave. Resources are limited and we have a tax cap. We can’t just look at these things strictly in isolation.”

Wheelabrator: Affordable option to recycling

The Department of Public Works sought bids and found a solution—the Wheelabrator.

“Manchester recyclable materials now go to a waste-to-energy facility located in Concord,” said Newton.

“It’s essentially turned into steam, which then powers approximately 15,000 homes and businesses in New Hampshire,” said Newton.

Located just off exit 17, the Wheelabrator power plant incinerates all types of waste—general household garbage as well as recyclables. Incineration appeared to be the least-bad option for Manchester when a contract with Pinard Waste Systems was due to expire, according to the department.

The members of the Special Committee on Solid Waste Activities recognized that they were searching for the lesser of various evils.

“It wasn’t an easy decision,” said Stewart. “Nobody liked the choices we had.”

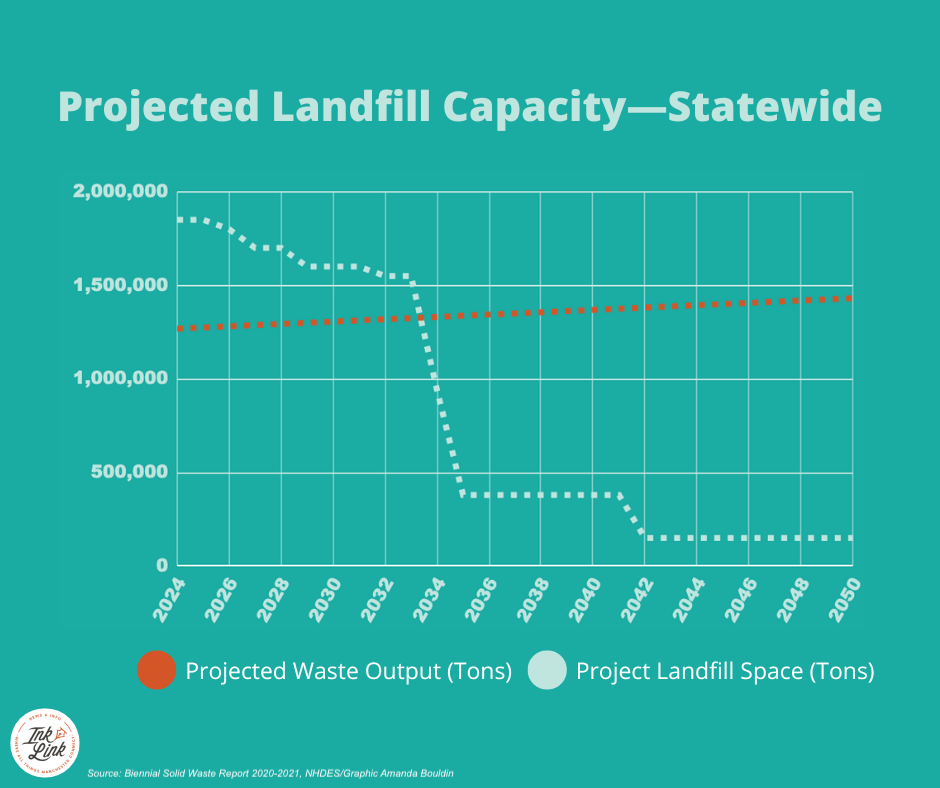

The least expensive option was to send the city’s recyclables to be buried in a landfill, but the committee was hesitant about contributing to increasing concerns over statewide landfill capacities, an issue that the state Department of Environmental Services has been tracking closely in recent years.

“We estimate that if no new permitted landfill capacity comes online, we would start to see a shortfall by 2024,” said Mike Nork, Materials Management Supervisor at NHDES.

In Manchester, Newton sees the incineration program as an affordable method of diverting recyclables from landfills.

“At the end of the day, if our recyclable material is going in a separate bin from the trash, it’s making a positive environmental impact,” said Newton.

However, NHDES sees things differently.

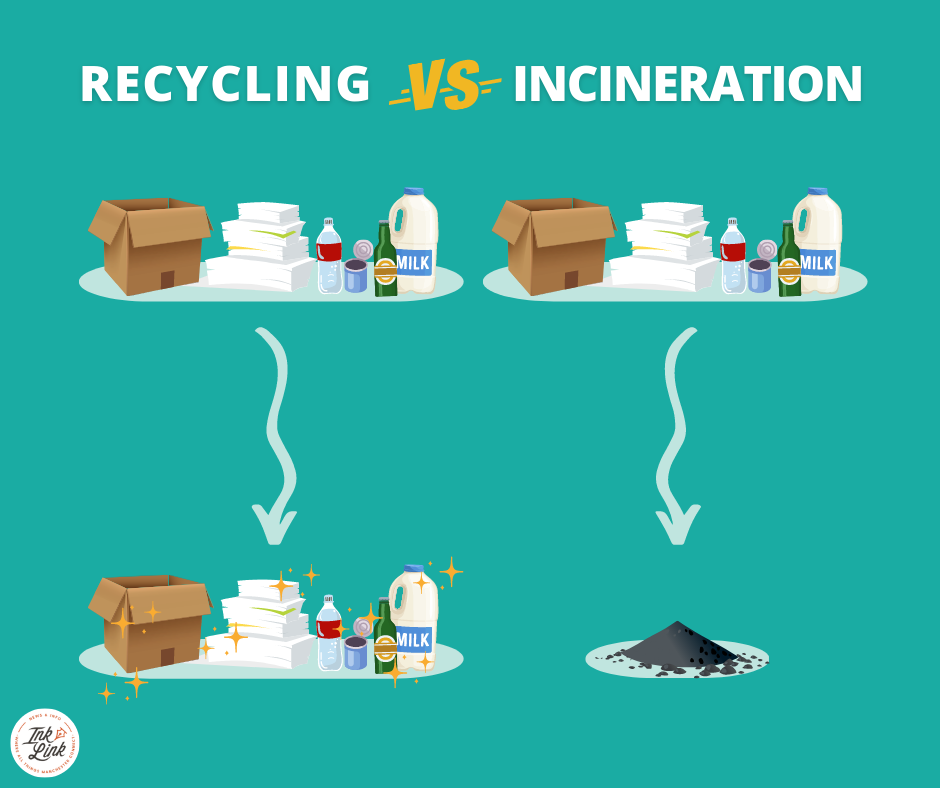

“Under the state definition of recycling, sending waste to an incinerator—even if you’re getting energy out of it—is not deemed recycling,” said Nork. “It’s still disposal. It’s unfortunate that Manchester is doing that.”

Reducing waste going to landfills is still important

Nearby Hooksett, however, has implemented an entirely different recycling program. Curbside recycling pickup has been suspended entirely, and residents must now gather and personally transport their recyclables to the transfer station, just like Spenard. Single-stream recycling is also off the table—residents sort each piece of recycling at dropoff. The benefit to all that effort? Tens of thousands of dollars in annual revenues from the sale of recyclables that were dropped off by Hooksett residents.

As for Spenard’s question about her personal devotion to making monthly visits to the Drop-Off Facility, Newton said it’s not in vain. Reducing waste going to landfills is still important. To that end, the city last year initiated a textile recycling program through Helpsy in an effort to encourage residents to stop tossing clothing in the trash.

Textiles make up about 6 percent of Manchester’s 38,000 tons of rubbish that ends up in a landfill every year, according to city officials. Estimates indicate that the Helpsy program can divert as much as 129 tons a year from the city’s waste stream.

“We do bring the cardboard and paper to a material recovery facility,” said Newton. The rest—mixed aluminum and plastics—go to the Wheelabrator. Cardboard and paper brought in for recycling is the only recyclable that doesn’t get incinerated. All curbside recyclables picked up by the city, including paper and cardboard, go to the incinerator along with other mixed recyclables.

When the five-year Wheelabrator contract expires, Manchester aldermen will again be looking for creative ways to protect landfill capacity and encourage recycling within the limits of the city budget.

“I would love to see the city get back to recycling,” said Stewart.

Spenard says she has reservations, now knowing that not all of her recyclables are actually being recycled.

“What’s it doing to the air?” she wonders. “I feel like I will still bring it to the Drop-Off Facility. It’s just not the answer I wanted to hear.”

Got a question you’d like to know the answer to? Send it to publisher@manchesterinklink.com and we will try to find you the answer.