Counting Cops, Part 2

Special 5-part series produced by Concord Monitor, a member of

READ Part 1 ⇒ Growing ranks: The number of NH police officers has grown twice as fast as the population over the last 20 years

On New Year’s Eve, some 1,000 people living in the small town of Hill quietly lost their police department.

At the end of December, Hill Corporal Andrew Williamson resigned after the town tried in vain to hire a new chief. The only other officer was on medical leave. The part-time police department had never offered 24-hour coverage, but Williamson’s departure left the town with a decision: should they increase their budget to find a new chief, or eliminate the local department altogether?

While big cities across the country have had raucous debates about defunding the police, in small New Hampshire towns the abolition of a police department can happen when a town simply votes to stop funding a department or is unable to staff one or two positions.

Former Alexandria Police Chief Donald Sullivan has recently been working for Hill to plot options for a way forward, and to take care of statutory requirements like handing off pending criminal cases and reports of child abuse to other law enforcement while the town lacks its own police force.

In a report presented to the Hill selectmen in June, Sullivan wrote that the town had four options: disband the department, hire a full-time chief and part-time officers, hire a part-time chief and part-time officers, or contract with a neighboring town. He analyzed 10 similarly-sized towns with a combination of part-time, full-time and no police departments.

In a report presented to the Hill selectmen in June, Sullivan wrote that the town had four options: disband the department, hire a full-time chief and part-time officers, hire a part-time chief and part-time officers, or contract with a neighboring town. He analyzed 10 similarly-sized towns with a combination of part-time, full-time and no police departments.

“My opinion is that the town should budget enough for the full-time position,” Sullivan said at a selectmen’s meeting, which would include increasing pay by 30% to attract a candidate in today’s competitive market.

Hill’s police budget rose from $67,000 in 2011 to $95,858 in 2021. Sullivan advised offering at least $120,000 to hire a new full-time chief, bringing the town’s police budget to $150,000.

Hill residents will have a chance to weigh in about the future of their police department either at a public hearing or next year’s town meeting. Earlier this month, the selectmen had not yet made any decisions.

Disappearing departments

While the number of full-time police officers in New Hampshire has grown by one-fifth over the past two decades, that growth has not happened consistently across the state.

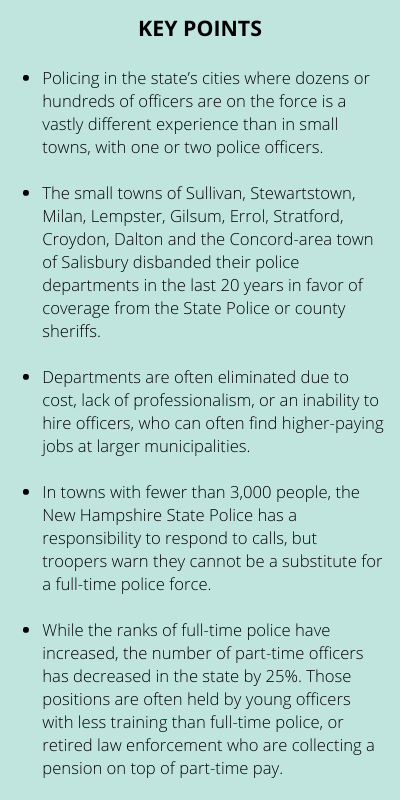

Since 2000, some towns have eliminated their departments in favor of coverage by the New Hampshire State Police or by local sheriff’s deputies. Towns that have eliminated their police departments in the last 20 years include Sullivan, Stewartstown, Milan, Lempster, Gilsum, Errol, Stratford, Croydon, Dalton and the Concord-area town of Salisbury.

Lempster Administrative Assistant Robin Cantara said the town voted to get rid of its police department around 2007. The Lempster select board is happy with coverage from the Sullivan County Sheriff’s Office, whose service the town has found to be cheaper, more reliable and more professional than its own police department.

“There’s no town agenda when there’s the sheriff’s department,” Cantara said.

Some voters eliminate their departments after tension between town officials and police departments boil over. In Salisbury, the town got rid of its department after both part-time officers resigned, citing a hostile work environment.

The most extreme New Hampshire case of town and police conflict occurred in Salem, where the police department was the subject of a critical 2018 audit that outlined police leadership’s disregard for the town manager’s authority, among other internal issues. Salem’s police department grew 8% between 2010 and 2020, adding five new officers. The town did not provide the number of police at the department in 2000.

Following the critical audit, Sgt. Michael Verrochi posted on his public Facebook page: “Wolves don’t lose sleep over the opinions of sheep.” He remains one of nine sergeants and 64 full-time officers at the department.

Regional solutions

Other towns like Temple and Greenville have combined their departments to save on costs while maintaining a local police presence.

In 2004, Greenville voted out its police department at town meeting and pitched neighboring towns on a merger.

Temple Police Chief James McTague had worked as a prosecutor in Greenville in the 1990s, and a friend asked him to consider it. While McTague was initially hesitant to get involved, he took a look at the numbers and was amazed. After residents approved the merger in March 2005, Greenville saved more than $150,000 in the first year, while Temple saved $60,000.

Officers got raises and Temple did not have to build a new police station. The two towns save on insurance and administrative costs and split the cost of big purchases like cruisers. The Temple-Greenville Police Department currently has four full-time officers and four part-time officers.

Seventeen years after the merger, McTague estimates that the two towns have saved $4.5 million, while crime declined 74%. When he visits other towns to share his experience, he said he sometimes sees pushback, including from police chiefs that don’t want to lose their jobs. But the main obstacle is something more emotional.

“They can’t get over one thing,” McTague said. “I’ve coined the phrase ‘the sandbox mentality.’ They don’t want to share their toys. It cracks me up.”

In towns with fewer than 3,000 people, the New Hampshire State Police has a responsibility to respond to calls, but troopers cannot provide all the proactive policing or attention to minor crimes that some residents want. State Police Troop D covers all of Merrimack County’s 25 towns and two cities, and is responsible for covering Salisbury, which has no police department, along with other small towns that have less than 24-hour coverage.

While county sheriff’s offices have become more involved in police work over time, they do not have the bandwidth for routine patrols.

“The idea of combining or regionalizing, whether it be combining departments, I think it’s a great idea,” Hill’s Sullivan said in an interview. “You can pool resources and have more resources available for any particular area. The theory is, you may not need somebody on duty in Danbury and somebody on in Hill at the same time, but somebody can cover both towns if there’s an emergency call.”

The towns of Danbury and Alexandria considered a police department merger this year, but Danbury voted against it.

By taking a regional approach, towns can save on computer software, as well as paying supervisors, dispatchers and secretaries. For some small and cash-strapped communities, that could be a long-term policing solution.

Part-time or full-time?

Between 2000 and 2020, the number of full-time officers has steadily increased in New Hampshire, but the number of certified part-time officers has declined by 25%. Trading part-time positions for full-time ones increases costs in both salary and contributions to the New Hampshire Retirement System.

A subcommittee of the Police Standards and Training Council is now evaluating the role of New Hampshire’s part-time academy program after the final report from the New Hampshire Commission on Law Enforcement Accountability, Community and Transparency raised questions about part-time certification. The subcommittee is trying to decide how to amend the program and whether it should continue at all.

New Hampshire’s part-time police officer certification requires 220 hours of training, compared to 750 for full-time officers. However, part-time officers have all the same powers as full-time officers.

“There are no limitations on the officer who has received less training,” said John Scippa, director of the Police Standards and Training Council. “To that end, we really need to recognize that police work is a job that requires a certain level of training.”

Hampstead Deputy Chief Robert Kelley said he believes the growth in full-time officers across the state has occurred as policing in New Hampshire has “professionalized,” with higher standards requiring an officer with more time to devote to police work.

Hampstead currently has nine full-time officers and seven part-timers, plus two “specials” – often retired officers, who work part-time hours.

Kelley said full-time officers serve communities better because they are more present and connected to people in town. They are more likely to recognize a car involved in an accident and better able to do follow-up the next day than an officer who is only around for a weekend shift.

When the part-time program began in the 1970s, it was meant to help agencies augment their police forces, Scippa said, but over time a few municipalities have replaced full-time positions with part-time ones.

McTague said he is disappointed that the state seems to be moving away from part-time certification. He appreciates that he can hire green part-timers before promoting talented officers to full-time positions.

It’s not just early-career officers who work part-time. Some older officers and chiefs retire from full-time roles and continue working part-time while collecting a pension.

The Police Standards and Training Council’s examination of the part-time certification is happening against a backdrop of police departments everywhere struggling to retire and retain officers, which puts departments like Hill in an uncertain place.

Sullivan believes the appeal of going through training and re-certification for a part-time gig has declined. “There aren’t part-timers anymore,” he said.

Coming Wednesday ⇒ Few NH police departments collect demographic data, but those that do are overwhelmingly white and male

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.