Not counting Nero, the most superfluous musical performance in history took place 70 years ago this week. Jess Stacey and his Famous Orchestra were playing at the Bedford Grove, but the boys in the band might just as well have left their instruments at home.

Who needed music?

In downtown Manchester, they were already dancing in the streets.

It was Aug. 14, 1945, and the war was over at last.

V-J Day had arrived.

After an anxious week of false alarms – a week in which hopes had been raised and dashed almost hourly – a radio flash at 7:03 p.m. caught the ear of an unknown soldier. He jumped from his table at the Puritan Restaurant and stepped onto Elm Street. His cry, according to newspaper accounts filed by Cpl. Norman Leighton, was simple: ”The war is over!”

He should have been a headline writer.

The ensuing celebration was the most joyous in Manchester’s history.

Even though seven decades have passed, those who were there will never forget the unplanned pageantry, the crying, the laughing, the tears and the cheers.

”I’ve never seen anything like it, before or since,” the late attorney Emile Bussiere once told me. He was a 13-year-old hawking copies of The Manchester Leader alongside Frank Young in the midst of the maelstrom.

”One has to remember that back in those days, radio was the only means of electronic communication,” he said, ”yet there was no suggestion that people congregate on Elm Street. People just found their way there on their own, and what I will always remember is the feeling of euphoria.”

Frank Young felt the euphoria. And claustrophobia.

”I was tiny then, and all I could see was ankles. I thought I was going to get crushed,” said Frank, who eventually gave up the newspaper trade and went on to become an attorney in White Plains, N.Y.

”Anytime there was a big event during the war, like D-Day or VE Day, I’d take all my money and buy as many papers as I could,” he said. “Normally I’d run through the Millyard to sell them, but everyone was on Elm Street. The paper sold for a nickel a copy, but that night, I was getting a buck apiece from people. They were just so happy.”

The newsboys were at the juncture of Hanover and Elm Streets – the hub of the hub-bub – along with thousands of others. It was a proverbial sea of humanity, and oceans of emotion spilled over. People felt an unspoken need to share the moment with others, people like Paula (Sandmann) Schulz, whose husband, Bill Schulz, was away in the Navy.

”Maybe it’s because we were all so excited about our husbands coming home,” she told me a while back, ”but we just looked for friends and walked and talked with anyone we saw the whole length of Elm Street.”

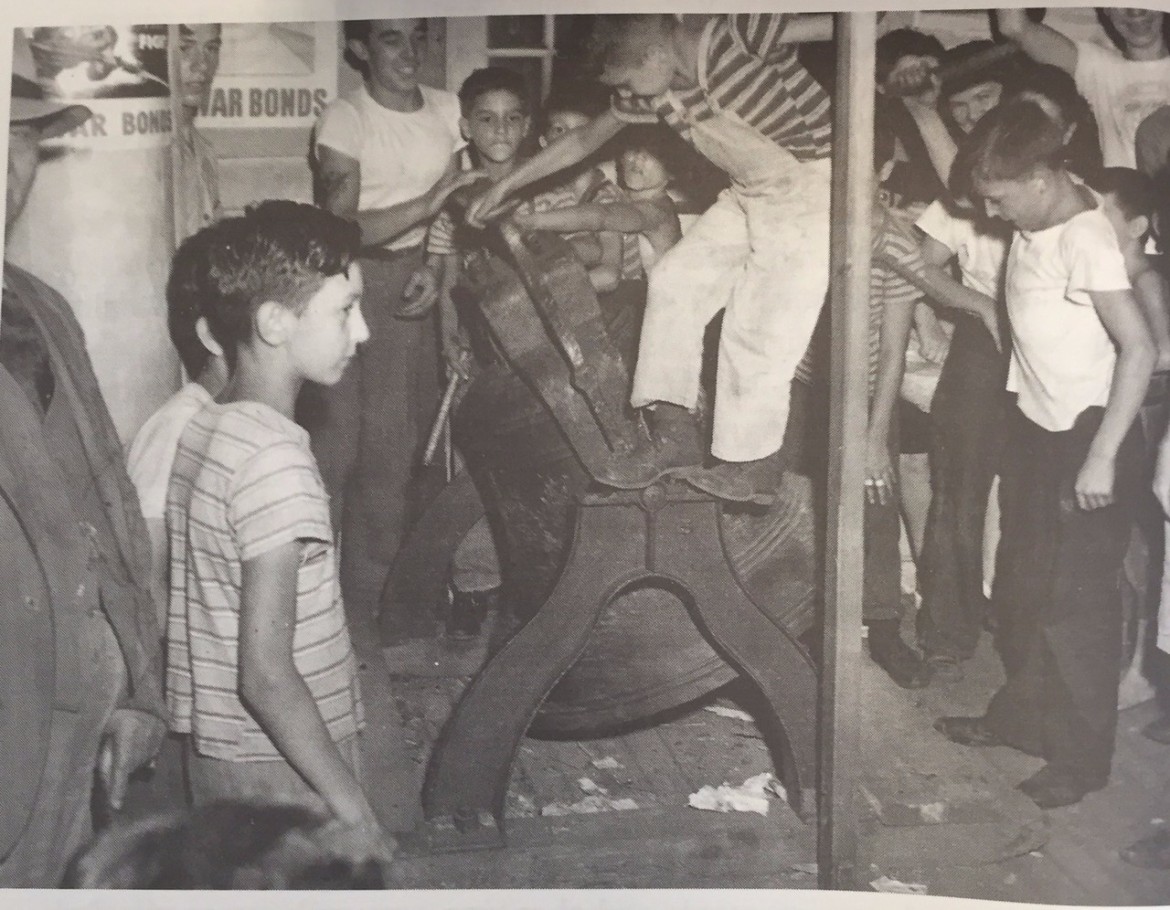

It was hard to be heard over the din. Air raid sirens wailed, church bells pealed and fire horns pierced the muggy summer night. At the Merrimack Common, kids clamored to clang the liberty bell at the Freedom House and car horns blared from ”the Elm Street jalopy parade” that materialized as if by magic.

There was no time for ticker tape, so people improvised. From a third story window in the Week’s Block, a young boy shredded newspapers and let the litter flutter to the ground. Others – mindful of the wartime paper shortage – made counterfeit confetti out of bread crumbs while still others filled the air with cursory concoctions of dry rice and beans.

Popcorn was added to the mix when moviegoers began pouring out of The Rex Theatre, because no movie – not even Roy Rogers in ”The Lights of Old Santa Fe” – could match the excitement outside.

The debris rained down upon the milling multitudes as Elm Street was quickly clogged. A horse and wagon laden with revelers clattered down the cobblestones after rolling all the way in from Pinardville, and the growing ranks of celebrants were swelled even further by the arrival of night-shift mill workers who’d been furloughed for the festivities.

First it was Holton Process that freed its workers, then Chicopee. Then Raylaine Worsted followed suit, as did Textron and MKM and Arms Textile, and, when the Waumbec workers left their looms and made their way out of the Stark Street gate, the uphill exodus was on in full.

”From then on,” wrote Fred E. Beane, ”it was one continuous howling, dancing, singing, yelling mass of humanity mixed up figuratively and literally with all the motor vehicles and bicycles in the city, about all the baby carriages, most of the babies, all of the good looking gals in town, soldiers and sailors by the hundreds, every kid in town.”

Even a kid like Bob Cloutier, who was 15 at the time.

”We were playing in the basement of Phil Gelinas’ house at 356 Walnut St.,” Bob told me, ”and as soon as we heard the news, we all went running down to Elm Street. We figured that’s where the excitement was.”

And how did Bob define excitement?

”Well, we figured we’d get kissed by all the girls,” he laughed, ”but we were only 15 so they pretty much ignored us.”

But the girls?

You couldn’t ignore them. With their beaming smiles and their lipstick just so and their short sleeved summer dresses and the thin black line drawn up the back of their calves, because there weren’t any nylons in the entire country, even for special occasions like this.

Meanwhile, even as hundreds of youngsters were hanging on the idling cars, others were hanging effigies of Hirohito and Tojo from a makeshift gallows in front of City Hall.

”Other cars were dragging the emperor in the rear,” Fred Beane wrote, ”and others just had stuffed images tied atop their mudguards, much as the proud sportsmen tote their deer southward from the New Hampshire woodlands in early winter.”

Wily officials tried to curtail the carousing by immediately closing the liquor stores and private clubs, but as one reporter noted, ”It’s a difficult task to shut off beer or liquor supplies from determined Yanks, and some who had stocked up in advance were full of good cheer as a result.”

At least one man was too full.

Acting Police Chief Walter Guiney said the man ”had been celebrating somewhat seriously and thinking he was at home, went to sleep on the Merrimack Common. This act in itself wasn’t serious except that he was found by Officer Daniel Wade without any pants, shoes and stockings on. He said he could not remember how he got there.”

At least he wasn’t adding to the pedestrian congestion on Elm Street. Once regular police and the MPs were finally taxed to the max, County Attorney J. Vincent Broderick was abruptly drafted to direct traffic at Hanover and Elm.

Given the gridlock, it was an easy job.

Yes, to a working class city grown weary of war, it was time to celebrate. The only thing that was moving was the very scene itself.

John Clayton is Executive Director of the Manchester Historic Association. You can reach him with your historical (or existential) questions at jclayton@manchesterhistoric.org.

You’re one click away! Sign up for our free eNewsletter and never miss another thing