Lord, I wish I had been the reporter assigned to the police beat at the Daily Mirror and American back in 1899. That’s when one of the great crime stories in New Hampshire history was unfolding right here in Manchester.

The date in question was Jan. 6, 1899, when 40 of the city’s most hardened criminals were, according to The Mirror, “Taken Unawares by the Supreme Court Authorities” and charged with the most heinous of crimes.

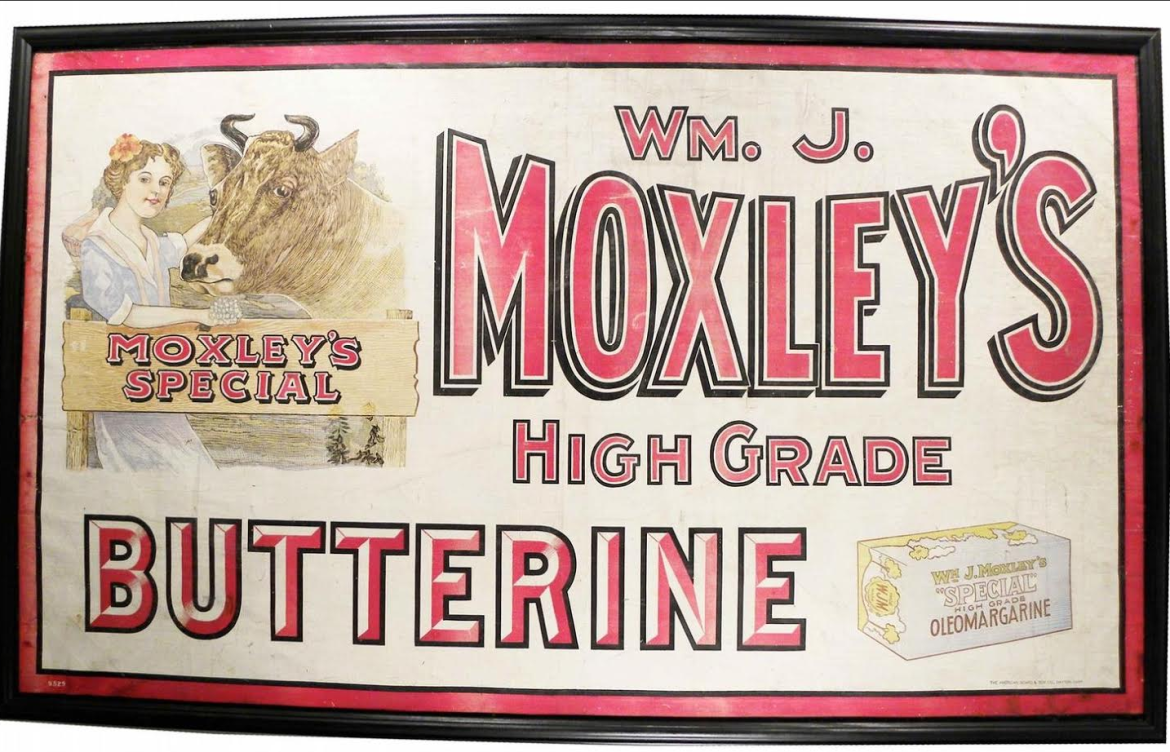

The offense? The 40 defendants were accused of serving “butterine” to unsuspecting diners.

In case you can’t find your dictionary, I’ll just tell you that butterine is what we know today as margarine, and back in that day and age, there were people in these parts who thought that butterine was on a culinary par with hemlock.

Yes, back in 1899 – when cows may well have outnumbered people in this dairy-intensive state – New Hampshire had strict laws regarding butterine, which is why the Manchester crime wave was front-page news.

“Considerable of a sensation resulted when it became known that these 40 cases were all against Manchester boarding house keepers or store keepers for alleged violation of the oleomargarine law,” The Mirror reported.

“The list takes in many of the largest boarding house keepers in the city,” the paper added, “and the round-up is the most general that has ever been known here.”

So how were people like William Cashin from the Star Coffee House and Hugh Grieve from the Gem Lunch Room, and boarding house operators like Rebecca Gray, Eliza Lewis and Mary Hagan able to perpetrate this fraud?

I blame it on the United States Supreme Court.

Back in August of 1885, the wise and all-knowing General Court of the State of New Hampshire passed a law that was designed to protect innocent consumers from the evils of butterine.

Based on the belief that butterine was a vile, synthetic product fashioned from large doses of slaughterhouse offal, all created under horrendously unsanitary conditions – and with a sincere wish to protect the vital bloc of voting dairy farmers – the Legislature ordered that butterine could only be sold in New Hampshire if it was dyed pink.

I am not making this up.

According to The Manchester Union, “The law absolutely prohibited the manufacture, offering for sale or having in one’s possession oleomargarine unless it was colored pink and plainly labeled.”

So why pink, you ask?

“The pink colour wasn’t chosen at random,” according to a British-based Web site called Practically Edible. “A cow that is ill with mastitis will give pink milk. Back then, people were closer to the farm and would probably have made the association with the colour of bad milk.”

Clearly, the folks who crafted the New Hampshire law knew what they were doing, and according to The Union, “After the law was passed it was considered absolutely ironclad, and… the dairy men patted themselves on the back and metaphorically tossed bouquets at themselves and each other.”

The New Hampshire law was such a sensation that it was actually cited as the proper path for Great Britain to follow in the “Sessional Papers Printed by Order of The House of Lords” in 1887.

The New Hampshire law was such a sensation that it was actually cited as the proper path for Great Britain to follow in the “Sessional Papers Printed by Order of The House of Lords” in 1887.

Back here on the home front, thanks to a watchdog named N.J. Bachelder – he was secretary of the State Board of Agriculture – no one dared to sell anything but pink butterine.

No one but Clarence E. Collins, that is.

Clarence was the manager of the Swift & Company Provisions shop at the corner of West Cedar and Franklin streets. When it was discovered that Clarence was selling white butterine – he was quite brazen about it, mind you – Mr. Bachelder had him charged with six counts of violating the pink butterine law and fined $100 on each count.

Unfortunately, Clarence was acting at the behest of one of the largest meat-packing concerns in America – Swift & Company – and the company was itching to challenge the constitutionality of New Hampshire’s pink butterine law.

That law was struck down on May 23, 1898.

Free trade was the defining issue, but in Collins v. State of New Hampshire, 171 U.S. 30 (1898), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that mandating the pink coloring “naturally excites a prejudice and strengthens a repugnance up to the point of an absolute refusal to purchase the product at any price.”

The Supremes even engaged in some extrapolation – I love it when they do that – stating that, if New Hampshire could order that butterine be colored pink, it could also order that “it be colored blue or red or black.” Taking it one step further, the court wondered why a provision for adding an offensive odor would not be just as valid as one prescribing the particular color.

For those of you who are students of constitutional law, Justice Rufus Wheeler Peckham wrote the majority opinion in the 7-2 verdict, with Justices John Marshall Harlan and Horace Gray dissenting.

With the pink option off the table, New Hampshire’s next anti-butterine law required that “it only be sold in tubs, firkins, boxes or other packages, each of which has upon it, to indicate the character of its contents, the words ‘Adulterated Butter’ or ‘Oleomargarine’ in plain Roman letters not less than one half inch in length, and so made, placed or attached that they can readily be seen and read and not easily defaced.”

And still, the 40 city slickers from Manchester deceived their customers.

With the ever-watchful N.J. Bachelder driving the prosecution – “The evidence was secured by spotters who visited the different places and carried away samples of the butterine for testing,” The Mirror noted – the cases moved swiftly through the justice system.

In fact, all of those charged entered pleas of nolo and paid their fines, but one lunchroom owner was bold enough to offer a warning.

“After this,” he told The Mirror, only partly in jest, “we are going to watch our customers and anyone who attempts to lug off a sample of butter wants to look out for himself.”

John Clayton is Executive Director of the Manchester Historic Association. You can reach him with your historical (or existential) questions at jclayton@manchesterhistoric.org.

You’re one click away! Sign up for our free eNewsletter and never miss another thing.

You’re one click away! Sign up for our free eNewsletter and never miss another thing.