Original reporting by

Leanne Gladle is one of around 10 culinary students finishing her last semester of an associate’s degree at Lakes Region Community College (LRCC), where on March 23, hands-on instruction at the campus shifted to online.

Gladle is also one of tens of thousands of restaurant employees across the state temporarily out of a job as eateries paused their dine-in services in response to government orders, with some scaling back to take-out or deliveries. Many restaurants, unable to survive a lengthy shutdown, are closing for good, making these layoffs permanent.

She hopes the tourist economy will pick up soon, but these days, all bets are off. “I try not to read the news as much.”

The 35-year-old Laconia resident says she is fortunate among her class of 50. She can pay her bills; she has plenty of experience, having waited tables or prepped in kitchen restaurants since age 14. She worries about some of her other classmates who must complete apprenticeships this summer, but stay-at-home measures will likely prevent them from doing so.

“We’re going to need to play that [the apprenticeships] by ear to see what’s available,” says Patrick Cate, vice president of academic and student affairs at LRCC. Cate says coursework that’s supplemented with practical experience will need fine-tuning; the bigger challenge lies with the allied health programs because long-term care facilities and hospitals are not accepting clinical placements.

Leaders at the seven community colleges are finding creative ways to replace demonstration- or lab-based learning that isn’t easily duplicated online. They’re also reaching out to students, who for a variety of reasons — family demands, lack of finances, slow wireless broadband — struggle with not accessing supports on campus.

Community college students are more likely than traditional four-year college students to earn credentials towards a specific vocation. More than half have family incomes below $30,000, making an associate’s degree or certificate an affordable option to prepare for specific careers. However, with the surge in the state’s unemployment rate and no timeline to loosen lockdowns, the jobs they expected to land after graduation are on hold, as are improvements to their financial status.

Students in the welding program at Great Bay Community College in Portsmouth knew exactly what they wanted, says Sean Clancy, associate vice president of corporate and community education. “That’s 27 people who knew they wanted to start in September, graduate in July and be a welder by the end of the summer, which is a high demand occupation.”

However, until these students can safely get back into the labs, the welding program is on hold.

Meanwhile, the culinary program at LRCC forges on with what associate professor William Walsh calls his “blue apron drive thru.” Once a week at the school’s loading dock, students pick up a carton of ingredients to plate food at home. After watching a video on filet de porc farci lyonnaise (stuffed pork tenderloin), for example, they send a photograph back to the instructor and receive feedback.

“The bonus is they are actually having some food for their families,” says Cate.

Unlocking doors for some students

Facilities are closed at the community colleges to students, but some faculty and staff members find they need to occasionally unbolt the locks.

Penny Garrett supervises the library at LRCC and says she goes in about once a week to help students who need internet access or a printer. Elizabeth Lawton, executive assistant to the president, stocks the food pantry and opens it up to any student who requests by email, a more conspicuous avenue than when the campus is open and students walk by the door and pick up a pasta box with no questions asked.

At River Valley Community College (RVCC) in Claremont, James Allen runs the library but also lines the food pantry shelves with around 1200 pounds of food a month, which he says usually empties out before restocking. Once the campus shuttered to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus, health concerns or perhaps stigma kept people away from setting up appointments. “But now there’s a little bit of an uptick in people wanting to come out and grab stuff,” he says.

Kaitlin Smith, like many of her RVCC classmates, lost her job as a waitress and bartender. The unemployment and one-time stimulus checks will help pay the rent this month for her Concord apartment. Next month, she’s less confident. For non-perishable groceries, she relies on the college’s food pantry.

“You can just kind of, call him [Allen] and he will get it all [from the food pantry]. And you just have to go there and pick it up, which I think is incredible,” says Smith.

In this tight-knit community, Allen assesses the underserved students who can’t afford basic supplies. In the last week or so, he mailed up to ninety $50 Market Basket gift cards using COVID emergency funds from the Foundation for New Hampshire Community Colleges.

Tim Allison, who directs the Foundation, says the trustees allocated $50,000 to distribute across the seven colleges to supply Chromebooks, gift cards or whatever each college needs to help students financially. Allison says he’s also expecting another $40,000 grant from the NH Charitable Foundation’s Community Crisis Action Fund, which raised $2.6 million to provide critical services to nonprofits.

“We don’t want people dropping out because of the income loss,” says Allison. The funds may be allocated for tuition assistance. We want to reduce impediments, he says, especially for those about to graduate.

More than academic support

Research shows what students need most is not academic supports, but ancillary services like food and transportation, says Jennifer Cournoyer, vice president of academic and student affairs at RVCC. They also need access to mental health — without worrying about costs and long waits.

On April 10, five of the seven colleges launched the Better Help app, a Telehealth program that allows students to get in touch with licensed mental health clinicians at no charge. (LRCC in Laconia and NHTI in Concord offered existing platforms.) Less the 24 hours after announcing the service, 100 students registered accounts.

Many community college students lost jobs while others are working night shifts to be at home during the day with their kids. Stress levels are high among students, says Cournoyer.

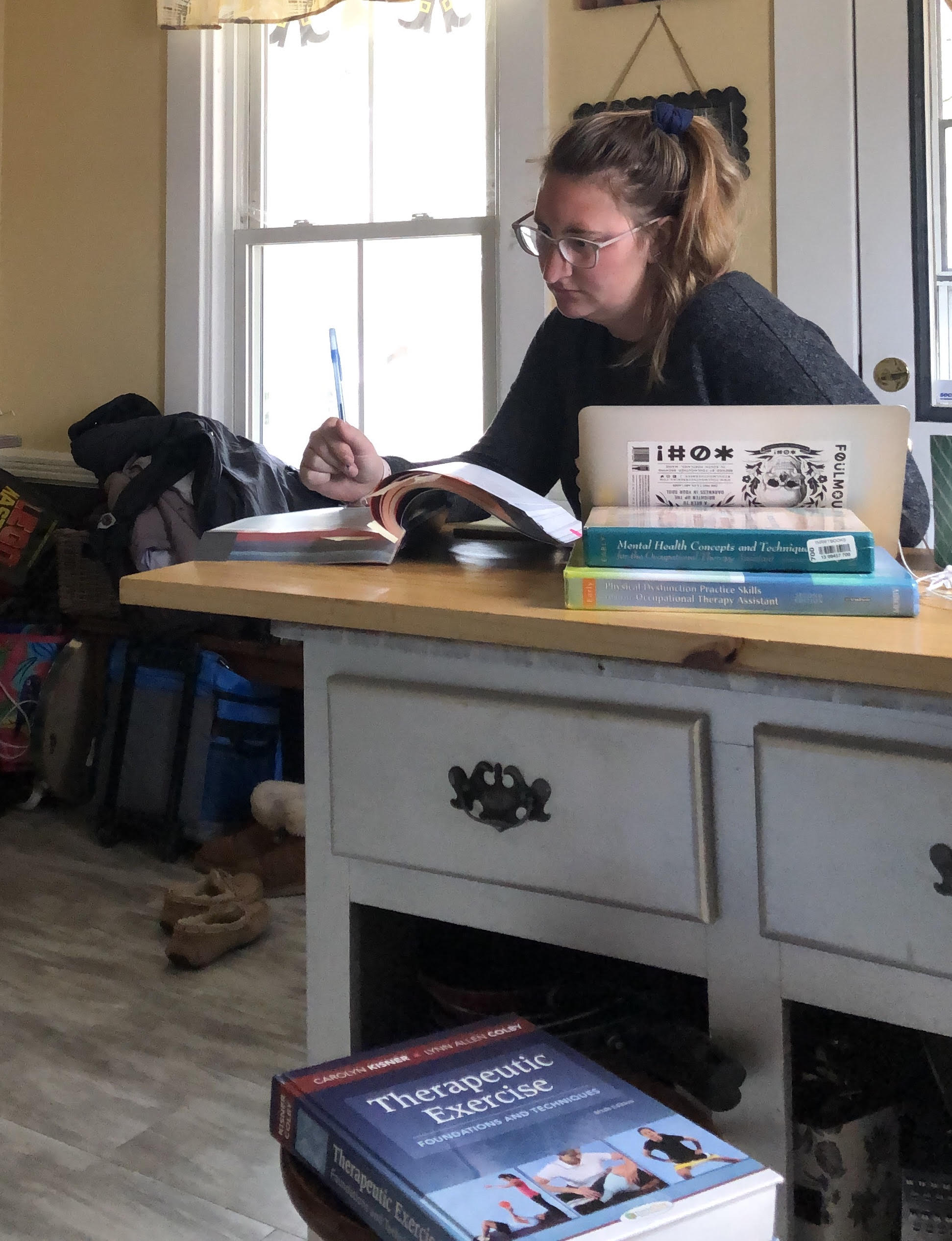

Kaitlin Smith, majoring in both physical and occupational therapy at RVCC, says she finds the service helpful. “Because when you’re home alone, a lot of thoughts go in your head and it’s nice to talk it out with somebody else.”

Practical experience moves online

In March, Smith was on her second clinical rotation for occupational therapy when her employer, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, put the brakes on her placement.

“We can’t continue on to take the board exam until we can go back to our [placement] site,” says Smith. “I’m basically stuck in limbo.”

To prepare for COVID-19 patients and to stop the spread of the virus, hospitals furloughed nonessential employees, including students. Ironically, this came at a time when facilities need more healthcare workers in the pipeline to address the crisis.

Some accrediting agencies are more lenient than others in requiring clinical hours, explains Denise Ruby, chair of RVCC’s nursing department. “Everybody is struggling to figure out how to get students to graduate.”

Virtual simulations can recreate a clinical experience, including caring for a patient. “It’s not really as warm and fuzzy,” says Ruby. “And you also don’t have the true connection with the patient.”

Some health education programs, such as occupational therapy, demand real time psychomotor scenarios: “You can’t practice teaching a kiddo handwriting without have a real little kid to work with,” says Kim-Laura Boyle, chair of health sciences for RVCC.

Looking ahead

With uncertainty about four-year colleges reopening in the fall, many families are rethinking whether to send their students away to institutions with high sticker prices.

This may spell opportunity for the seven community colleges, says Larissa Baia, president of Lakes Region Community College.

“We’re here for the student who will graduate high school this year, for the unemployed restaurant worker, for the single mom who has always wanted to be a nurse, for the veteran who wants to be an automotive mechanic or a firefighter.”

The pandemic-induced recession doesn’t change the mission of community colleges. “What is likely to change is how we carry out that mission.”

Baia says she expects schools to promote more courses that offer a hybrid of face-to-face and online instruction, more flexible schedules and shorter terms to quickly move people into the workforce.

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.