CONCORD, NH – “Do you know where my mother is?” “What’s going on?” “When can I go home?”

NH Circuit Court Judge Susan Ashley hears these questions regularly from children in her courtroom. Confused and scared, they come to court because they are at the center of the growing number of child neglect cases in New Hampshire that involve allegations of parental opioid abuse.

⇒ Read Part 1: Child Welfare & Opioid Addiction, Part 1: Striking a Balance of Protection, Treatment

Although infants and toddlers are entering state care due to safety concerns at alarming rates, child welfare experts expect that older children whose parents are severely addicted to opiates are the ones who are likely to suffer the most as a result of the ongoing addiction crisis, and who will put the most strain on foster care systems. Some of these children will be shuffled from one foster home to the next, until they eventually age out of the system, never outgrowing the hypervigilance that comes with watching over a parent who is high on heroin or sick in withdrawal.

“There’s always a sense of urgency in these cases,” says Ashley, the lead judge for the NH Model Court Program, which develops statewide guidelines to improve outcomes in child abuse and neglect proceedings. “The children need to have stability in their lives, and we have to continue to search for that for them, and try to be sure we are giving everyone the due process they are entitled to, and then move forward in a difficult situation.”

“There’s always a sense of urgency in these cases,” says Ashley, the lead judge for the NH Model Court Program, which develops statewide guidelines to improve outcomes in child abuse and neglect proceedings. “The children need to have stability in their lives, and we have to continue to search for that for them, and try to be sure we are giving everyone the due process they are entitled to, and then move forward in a difficult situation.”

In some cases of child abuse and neglect, when the court has entered a finding of neglect, children remain at home during the 12-month period the law allows for parents to remedy the problems the court identified, before the judge decides whether to terminate parental rights. In other cases, however, the NH Division of Children Youth and Families (DCYF) deems it necessary to remove children from their homes, due to concerns about their safety, and place them either with relatives or in foster care.

Increasing Caseloads

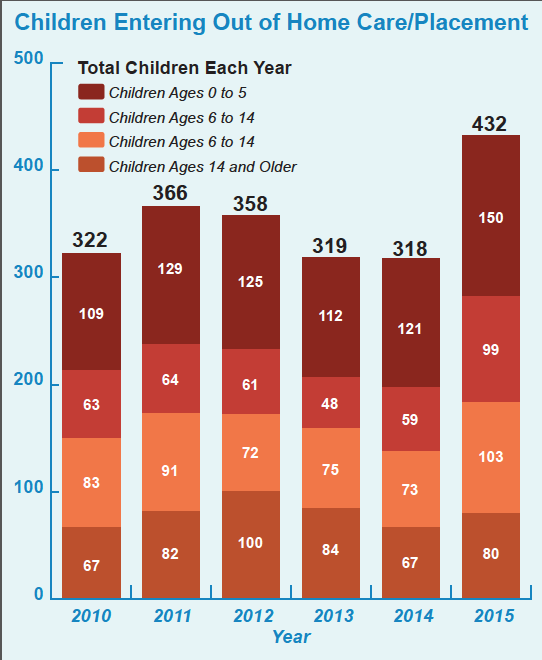

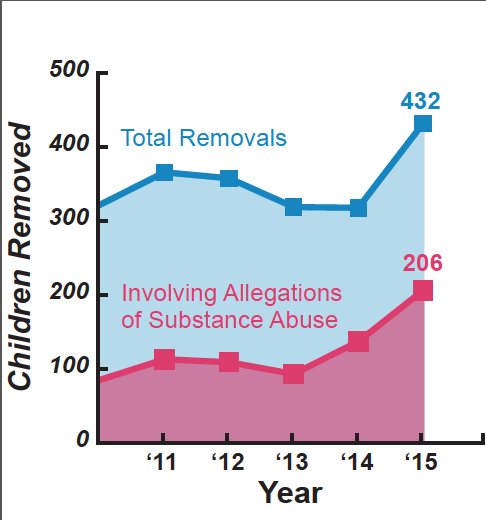

Between 2014 and 2015, the total number of children removed from their homes by DCYF increased 36 percent, from 318 to 432, according to agency statistics, and almost half of all child removals in 2015 involved allegations of parental substance abuse, drug abuse, or poisoning/noxious substances. The number of children ages 12-14 who were removed from home nearly doubled, from 25 in 2014 to 44 in 2015. In addition, the recent passage of Senate Bill 515, which is designed to make it easier for DCYF to intervene in cases of parental opioid abuse and dependence, is quicken the pace of these trends.

Meanwhile, DCYF remains understaffed to handle the increasing caseloads, and the state’s foster care system only has about half of the foster placements that are needed, says Kathleen Companion, DCYF foster care program manager.

“I think, ideally, we should double our number of foster homes,” Companion said. “Less than 100 of the families have openings, and those might not be in the community where we want the child to stay, or sometimes the child has specific needs, and the family can’t meet those needs. Many of these families also have their own children, and the foster kids can be aggressive or have behaviors that could make their own children unsafe, and we have to be able to make the right match for the child.”

The need for more foster families in New Hampshire, as well as for more DCYF workers to match children with foster homes and process foster care licensing applications, is expected to intensify as the opioid addiction crisis continues. Christopher Wildeman, an associate professor at Cornell University who serves as co-director of the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, is an expert in child welfare and foster care.

“It’s hard to put a number on how much it’s going to impact foster care caseloads because it’s so early on,” he says of the nationwide opioid addiction problem, “but if things keep on going the way they are, I think we can expect a 10 to 20 percent growth in foster care caseloads over three to five years of similar increases in opioid addiction rates.”

Providing foster care for babies is presenting unique challenges to DCYF and child welfare agencies across the country, as the number of infants in state care increases – 150 children under 2 years old were removed from New Hampshire homes in 2015, up from 121 in 2014. But in cases in which parental rights are terminated, the state is often able to see these children adopted by families in New Hampshire, or across state lines when necessary. That is not true for older children.

When an older child of an addict enters the foster care system and waits a year as his mom attempts to get clean, if a judge eventually terminates parental rights, the child is, in some cases, “essentially unadoptable,” Wildeman explains. The court then holds regular review hearings as DCYF and others attempt to locate a family member or adoptive home for the child, which can take years. And those efforts can fail, leading to the designation “another planned permanent living arrangement” (APPLA). Once viewed as a system failure, APPLA designations are now accompanied by more intentional permanency plans, using protocols developed through the Model Court Project.

Children’s Voices in Court

In 2008, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges selected the 6th Circuit courts in Franklin and Concord as one of 36 Model Court sites in the country. Through the work of multidisciplinary teams, these sites act as laboratories for developing best practices in child abuse and neglect cases, including in crafting permanency plans for APPLA youths. The NH Model Court project also developed guidelines in 2012 that stressed the importance of timely court filings, expedited hearings, and child participation in court proceedings. These guidelines help judges gather more information as they make difficult decisions about permanency.

Judge James Carroll was skeptical at first about asking already-traumatized children to enter the court setting, but he has found both their input and their energy to be an important part of a challenging case type. “Quite frankly, to me, it’s the best time of all,” says Carroll, who also presides over a criminal drug court – which he refers to as “recovery court” – in Laconia. “No matter what the children have been through, they’re just the most amazing, insightful and abundantly mature people.”

The judicial process for civil abuse and neglect cases and the statutes that govern it are based on research into the need for attachment and stability in a child’s life, says Judge Ashley, who regularly presides over child abuse and neglect cases in Rochester. In the life of a child, a year in an out-of-home placement can seem like an eternity; for an opioid addict, a year can drift by as priorities gradually shift from using drugs to reunifying the family. These cases are a race against time for parents, and for an addict whose DCYF involvement acts as a wake-up call and a potential bridge to substance abuse treatment, the call sometimes is not heeded until it’s too late.

“There are people who wait, because they’re not ready (to get into addiction treatment),” Ashley explains. “We talk to them and let them know the clock is ticking and what could happen, but they are in a situation where they are not focusing on anything besides their use, so they don’t make efforts to get into treatment until very late in that time, and they have to ultimately live with the results of that, and that can be very difficult.”

To address these situations, some state legislatures have passed laws that enable the reinstatement of parental rights in certain circumstances. In New Hampshire, grandparents are increasingly stepping in to assume guardianship of the children, to give the parents more time to get sober and make the necessary lifestyle adjustments to become effective parents, says Betsy Paine, staff attorney for Court-Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) of New Hampshire.

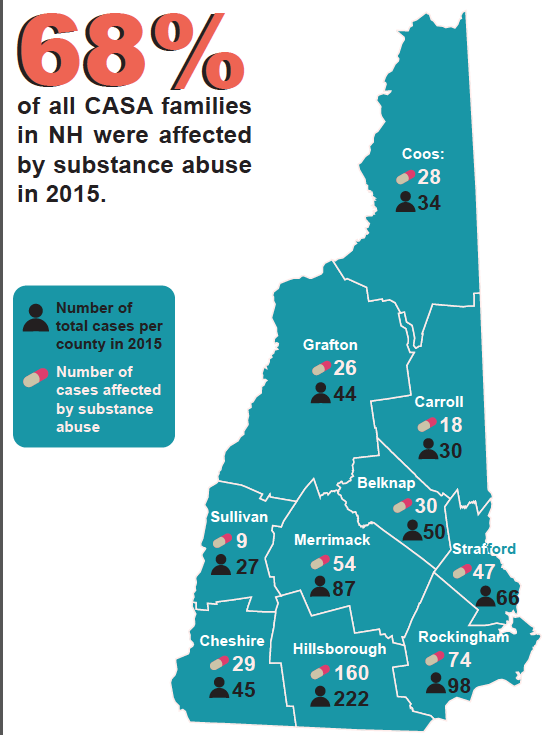

CASA is a private nonprofit whose mission is to recruit, train and support volunteer advocates across the state to represent the best interests of children in courtroom abuse and neglect proceedings. In 2015, 68 percent of the roughly 700 cases CASA was involved with statewide included allegations of parental substance abuse. CASA President and CEO Marty Sink says it may take years before child welfare professionals understand the full effect that living with opioid-addicted parents has on children. “We talk about treatment and recovery for the addict, but what kind of services are we providing for these kids?”

CASA is a private nonprofit whose mission is to recruit, train and support volunteer advocates across the state to represent the best interests of children in courtroom abuse and neglect proceedings. In 2015, 68 percent of the roughly 700 cases CASA was involved with statewide included allegations of parental substance abuse. CASA President and CEO Marty Sink says it may take years before child welfare professionals understand the full effect that living with opioid-addicted parents has on children. “We talk about treatment and recovery for the addict, but what kind of services are we providing for these kids?”

The Cost of Foster Care

Entering foster care is costly in terms of the emotional and mental health effects, but it also carries substantial financial costs for the state. For each child in a general foster care placement (many children in the system require higher levels of care), the state pays about $550 per month, which doesn’t include outside supportive services, such as counseling, transportation, and child care, according to Companion, the DCYF foster care program manager. To put things in context, Companion said the state had 778 children in protective custody on April 30: 645 were removed during abuse and neglect proceedings; of those, 252 were living with a relative, and 393 were in non-relative foster care, including 71 in individualized service options (ISO) high-need foster care; the rest were in institutions or group homes.

Foster parents providing general foster care receive between $15.80 and $27.20 per day per child, depending on the child’s age and level of need. Those rates were lowered in 2010, says Companion. Foster families that provide ISO foster care receive higher rates through independent agencies that contract with DCYF to recruit and support those families.

“We’re really trying to build therapeutic foster care in our state, where the actual foster parent would have the skills to work on these issues themselves with these children,” says Companion.

Wildeman has suggested one possible alternative to this expensive government intervention: “States really could think about transferring those resources not to placing kids in foster care necessarily but in providing treatment services to the parents, but in a lot of states, those pots of money are not connected, so it ends up being sort of a difficult issue to unravel.”

For now, child welfare officials, judges and others involved in the system are hoping that more people will step forward to provide foster care, serve as volunteer child advocates in court, and advocate for additional treatment and child protection resources and policies in New Hampshire.

CASA, which currently has about 400 volunteers statewide, is working to recruit 150 more. “That’s our goal, and that’s the state’s goal – that we are available for 100 percent of the need,” said Sink, the organization’s president.

Deb Urbaitis, a lawyer in Henniker, represents parents in abuse and neglect cases, but she also provides foster care with her husband, Todd. The couple recently took in a 6-year-old girl, who they hope to adopt. She says the state’s child welfare and mental health care systems are embarrassingly inadequate when it comes to meeting the needs of children who come into state care. “You have a whole system that is ridiculously overloaded,” she said. “I don’t know how they’re going to place or where they’re going to place all these kids.”

She says resources for foster care are strained, and the laws need improvement. “We can create better legislation to help foster parents, and we need some better education out there for everybody, including the people who work in social services,” she said. “There are some changes that need to happen for sure.”

Urbaitis says she thinks it’s important for attorneys to be aware of these issues, even attorneys who don’t practice family law. In addition to being influential generally, attorneys are uniquely well suit to become foster parents, she says, because they understand the system and can advocate in court effectively and with credibility. For her, although challenging, the process of providing foster care to needy kids has been extremely rewarding. “As foster parents, you have this chance to at least be on the receiving end when the kid does that walk up to the house – I call it the long walk – and you can say, ‘Hey, I’m here for you. We’re going to help you.’”

Part 2 of a two-part series republished with permission from the NH Bar News. Click here to see services available for the general public.

Part 2 of a two-part series republished with permission from the NH Bar News. Click here to see services available for the general public.